The announcement of the Banksyland tour – the first, international exhibition from the 21st Century’s most provocative artist, unauthorized as it is currently at Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Film/Woundworks from September 2-6 – brought about more questions than it could ever answer.

Beyond the eternal “Who is Banksy?” question to the possibilities of identity, Banksyland and I ask a bigger query: “Why and what is Banksy?” How does an artist with the stealth ability of a cat burglar and the street smarts and savvy of graffiti writer get away with implicating satirical work on walls across the world making serious sport of corporations, religion, money and the aristocracy while being awarded so much money at auction for that same cutting artwork?

Like Dadaist godfather Marcel Duchamp and Pop Art masters such as Andy Warhol – both of whom Banksy touches on with his readymade British telephone booth, his Warhol Monkey and his mock-Marilyn featuring model/one-time Johnny Depp paramour Kate Moss – the very nature of what art is/what is art comes into play. With Duchamp’s use of the everyday and the role of repetition in Warhol’s work, what does an artist’s anonymity matter? Why shouldn’t Banksy be nameless and faceless, a character in his own play?

Philadelphia Weekly, Culture.org and A.D. Amorosi will look at the phenomena of Banksy in several features across the next few days.

The (Humble?) Beginnings of Banksy

The (supposedly) working class, Bristol, England-born Banksy has been worming his way through the public’s consciousness (and up the nose of the staid culture of art curators and critical cognoscenti) since the early 1990s.

Refusing to give his (or her) name, the wily street artist with a snarky edge (and empathy) toward the messaging and symbolism of social consciousness and political activism has used the skill sets of stencilling and graffiti to make his usually satirically humorous points. That the incendiary work has been scrawled on the walls, bridges, doors and streets – first in Bristol, then globally as far afield as Palestine where he crafted nine images on the Israeli West Bank wall – maintains Banksy’s renegade street cred, a beloved tie to the universal underground.

Is it an underground, or is it, as The Guardian’s art critic, Charlie Brooker wrote “work [that] looks dazzlingly clever to idiots” and hipster audiences?

However, like the street-strewn works of New Yorkers such as the late Jean-Michel Basquiat and the late Keith Haring, work crafted for democratic public display where all could see, the work of Banksy is usually removed as soon as its finished, stolen and pirated away so to land in the hands of the very people that the artist is lampooning – and going for very high prices when they get to their new, private homes.

Selling The Bank(sy) Of England

How expensive is the art of Banksy? And what is it worth considering its scrawl across common walls and its move from pavements to penthouses?

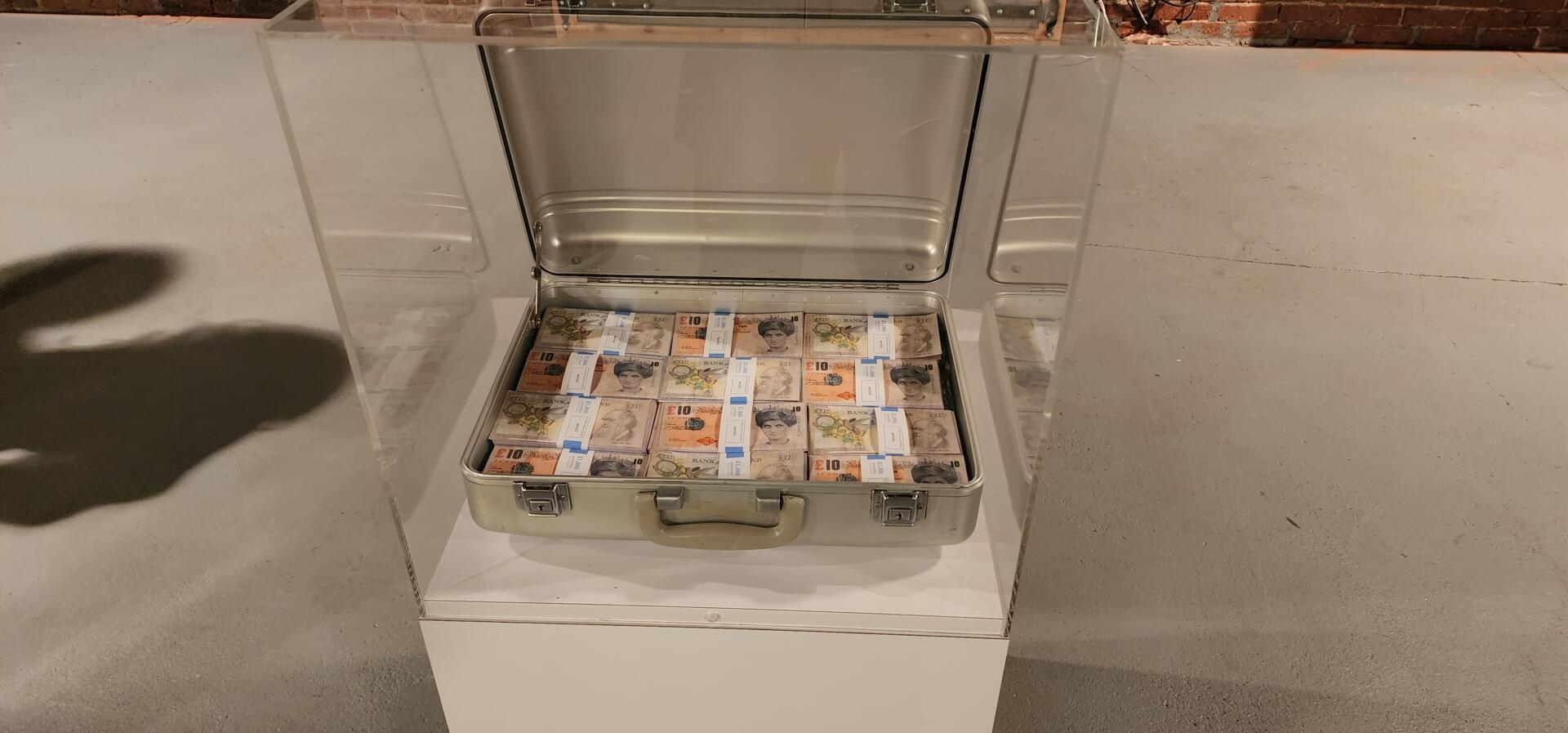

Along with, say, his own money and a 2004 series of spoof British £10 bank notes replacing the picture of Queen Elizabeth’s head with that of Diana, Princess of Wales’s head (changing the text “Bank of England” to “Banksy of England”) – a criminal offence in every country – works such as 2009’s Devolved Parliament have fetched just under £9.9 million at London’s Sotheby’s auction house (equivalent to around $11 million in US money today).

Obviously, buyers are hungry to see members of Parliament depicted as chimpanzees in the House of Commons, selling just in time for the UK’s Brexit debate in 2019. Painting for Saints or Game Changer depicting a hospitalized child playing with a toy nurse fetched £16.8 million in 2021. Then there is the first work in history ever created during a live auction, the 2018 Sotheby’s Auction House art prank where a framed copy of Banksy’s famous 2006 Girl with Balloon – sold for $1.4 million – was lowered into a Banksy-created shredder built into the bottom of the frame, and mostly torn into tiny little pieces with only the heart-shaped balloon remaining visible.

“Some people think it didn’t really shred,” Banksy wrote on Twitter. “It did. Some people think the auction house were in on it. They weren’t.”

Odder still, in 2021 at Sotheby’s, the shredded art work, re-christened Love Is In the Bin, sold at three times the price of its original – £18,582,000 – despite its estimated value of £4m-£6m.

To quote The Clash’s angry man, Joe Strummer, in “White Man in Hammersmith Palais” – “You think it’s funny? Turning rebellion into money?”

The Philanthropy of Banksyland

Money, however, is not at the root of Banksy’s agenda, supposedly, if we are to believe the curators behind the Banksyland exhibition.

Not only has no cash or renumeration been exchanged between artist and international exhibitor and organizer One Thousand Ways – yes, Banksyland is and remains “unauthorized,” but they are in steady contact with the artist and his Pest Control outfit – the representatives of Banksyland stress their philanthropic efforts along with that of its namesake as part of his people-first rhetoric.

That means selling work to raise funds for Campaign Against Arms Trade and Reprieve, the raffling of paintings to aid NGO Help Refugees and Greenpeace, the development of The Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem in support of Palestine, and the funding of rescue boat to save refugees at risk in the Mediterranean Sea.

Philanthropic, sure. Yet Banksy has enough money in reserve to keep himself unknown and anonymous, and does much in his power to retain the singular right and ownership of his images (beyond One Thousand Ways, other exhibitors of his work are out there, yet damned by Banksy with yellow and red ‘X’s on their sites) such as attempting to trademark his images without being forced to give his true name. Banksy may have once said that “copyright is for losers” as he has appropriated images from Warhol to Michelangelo…

That doesn’t mean that he likes living by that accord or court ruling.

What is Banksy, along with who Banksy might be, and what is he doing on tour in Banksyland? That’s the subject of our next feature, Welcome to Banksyland: Pictures at an Exhibition/Postcards of the Hanging.