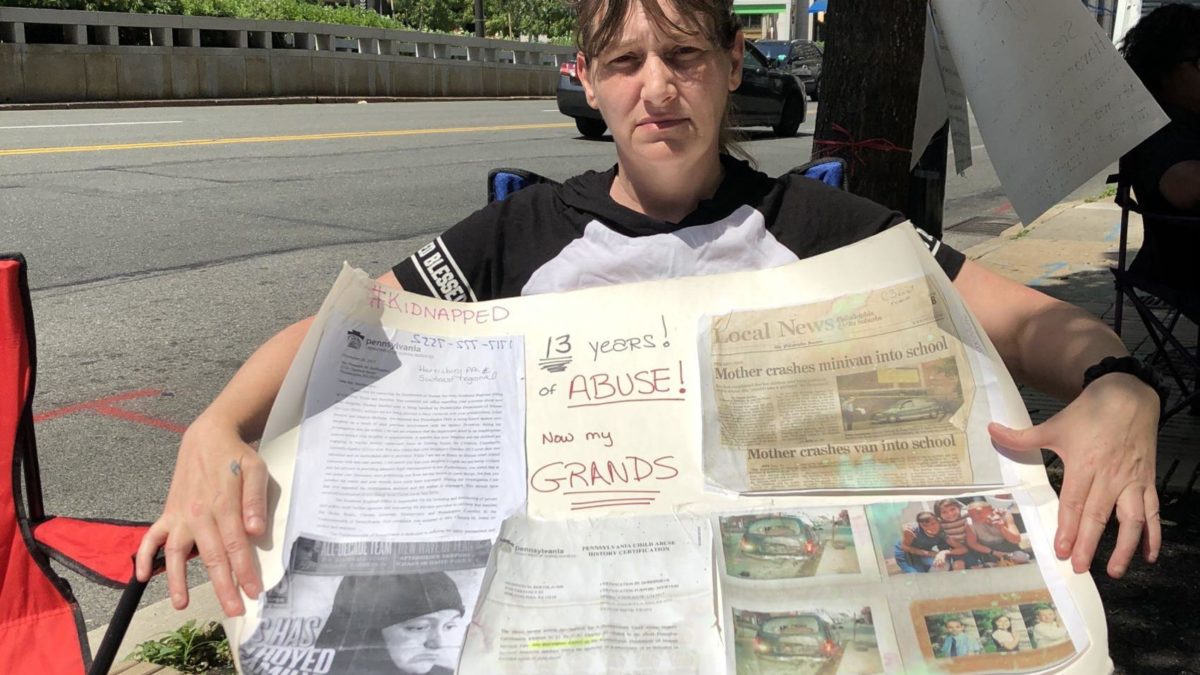

In 2015, someone called DHS because Miltreda Kress and her boyfriend had a loud, violent fight about two of her four daughters who were acting up.

“It got heated, and we admitted to all of it when that social worker come out in 2015,” Kress, of Holmesburg, said. “It was basically an open and closed case. He shook my hand and said, ‘If I had more parents who parent [as] you do, we would have an easier job.'”

Kress is strict. Her daughters go to school, come home, finish their homework and chores. Then, after dinner, they can do what they want to do, except leave the house on school nights.

Kress said they do hide snacks and ask the girls to make their beds. And if the girls get in trouble, they’re not allowed to go out; Kress takes away their laptops. She is a stringent but competent parent, Kress said.

But in 2017, DHS got an anonymous call accusing her and her boyfriend of child abuse and neglect. “The abuse came back unfounded,” Kress said. “But for neglect, they put in ‘inadequate supervision and improper care.’ My kids are always supervised. The schools used to tell me all the time that, ‘We wish we had more parents who were proactive like you.’”

But no social worker ever went to the girls’ schools to interview them about her parenting, and the DHS worker who visited her house after the anonymous call told Kress that she didn’t approve of her “militant style of parenting,” Kress said.

The three younger girls removed from her home have all been separated into different foster families. “My one daughter has been pushed from house to house to house and neglected and abused,” said Kress, who works for the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation.

And although Kress completed everything the CUA worker demanded of her to get her children back, soon her boyfriend came under fire.

“They tried to pin my fiancé as a pedophile” because he tried to help one of the girls in the middle of the night when she wasn’t feeling well – an incident Kress, herself, witnessed and said was totally proper.

“Ten years ago, I was a heroin addict. I got over that on my own, and this has been way harder not being able to protect my children the way I protect them,” Kress said. “Them not being home and not knowing where they are 24-7 is tearing me up inside.”

In the meantime, DHS continues to fracture families, not only sometimes removing children from parents for what many families say are flimsy reasons, but also often refusing to place children in the custody of kin – even when family members are willing and able to care for those children.

The DHS Parent Handbook explains that it is the city “agency charged with protecting children from abuse, neglect, and delinquency; ensuring their safety and permanency in nurturing home environments, and strengthening and preserving families.” The agency attempts to accomplish these goals through a community-based delivery service called Improving Outcomes for Children, in which case management services are delivered by local providers, designated by police district, called Community Umbrella Agencies.

“Through the CUAs, IOC ensures that children not only receive services in their own neighborhood whenever possible but that families have a single case point of contact (the CUA Case Manager) that coordinates all of the services they receive,” the handbook reads. “IOC also has a strong focus on Family Teaming, which ensures that the child, the family, and other caring adults are actively involved in planning and decision making. Thus, while DHS is responsible for investigating reports of abuse and neglect and removing children from unsafe situations, once your child enters placement, you will work directly with the CUA Case Manager to take the steps necessary to reunify your family.”

Sometimes the process moves smoothly. But in the reporting of this piece, many families told stories of being shifted around between CUA workers, a lack of consistent and clear communication, and the feeling among families that the goal is not really reunification. Occasionally, the process drags out so long that families give up out of sheer frustration and having been traumatized by the process.

In addition, court-appointed attorneys are often overworked and cannot put in the time to properly represent impoverished families. The high number of court visits required and the burden of the bureaucracy overwhelm some people trying to battle the system to get their children back or placed with kin. And then there’s the clause that says if a child has been in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months, parental rights can be terminated.

“For all the kids in foster care, over half are living with kin,” said DHS spokesperson Heather Keafer. “We want families to live safely together and to thrive.”

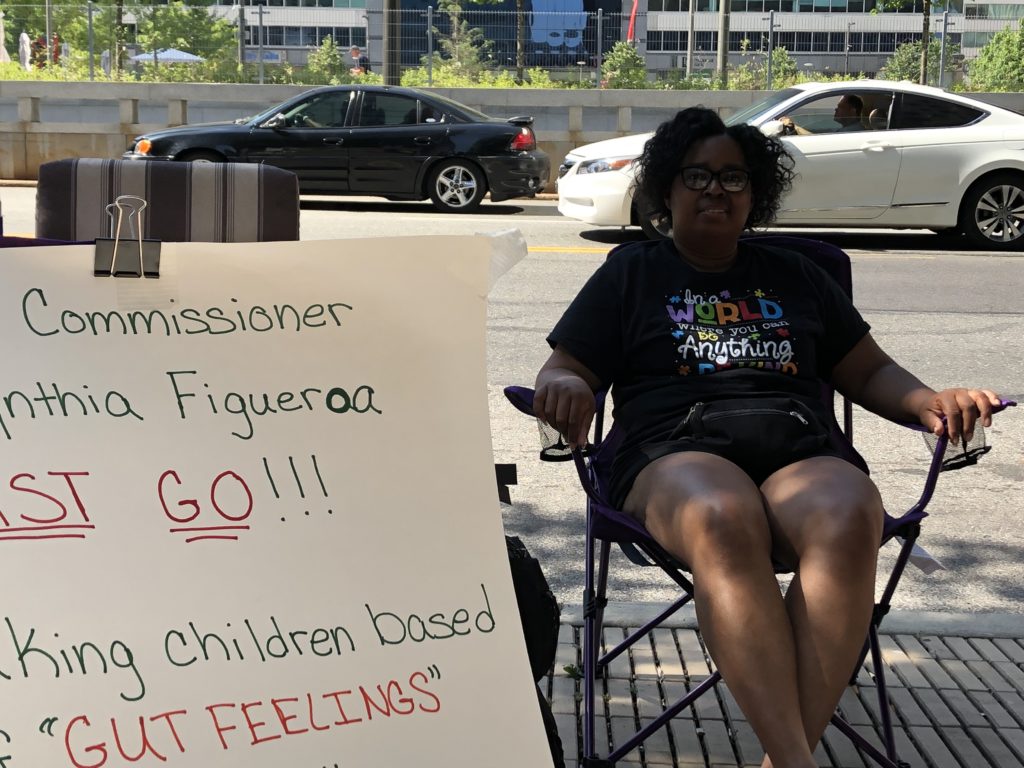

DHS commissioner Cynthia Figueroa agreed.

“Their [families’] voices are important,” the commissioner said. “Their experiences are real. Many come to the Child Welfare Oversight Board meetings, and we’re glad to have their participation there and also at the Quality Parenting Initiative that some are involved with. Given confidentiality, we are limited in what we can say, but understand that the complexity can create frustration for families. Our goal is to reunify families as quickly and safely as possible – our number one goal is to keep kids safe.

“Fifty-six percent of youth in family foster care were in kinship care,” Figueroa added. “Every case is individual. Both the biological family and the child have a voice. This does not always align with what another family member wants. DHS invests significant resources in locating family members, through processes like Family Finding and Accurint.”

But many families interviewed for this story said they do not feel that reunification is DHS’ actual goal.

Kress has been granted unsupervised visits with her daughters and has been doing family therapy in-home with her children. She is making progress, and DHS and CUA workers have been lately arguing for the reunification of the family – except the judge will not agree to send her daughters home unless Kress’ boyfriend “admits to things he didn’t do,” Kress said.

To make matters worse, Kress has also lost her house and landed in landlord-tenant court over L&I violations, so even if the judge were to say her daughters could go home, Kress has no place for them. At the time of this report, she, herself, is staying with a friend.

Kress said the social worker who came to her house in 2017 did not have a written court order, alleging instead that she had a verbal one and that she would call the police if Kress did not comply with turning over her three daughters.

“I feel I lost the day that woman knocked on my door,” Kress said.

Part III of ‘The Kids are Crying’ will appear in print in the Nov. 28 issue of Philadelphia Weekly, but you can read Parts I & III of this three-part series now on philadelphiaweekly.com.

This article is part of Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project among 23 news organizations, focused on Philadelphia’s push towards economic justice. Read more of our reporting at brokeinphilly.org.