As TJ Cahill tells it, he just “dares to care.” If you listen to a slew of local residents across the Philly Internet, he cares about as much as Mussolini did.

Whether he’s a hero or a villain is probably a litmus test about your personal politics, though. Or, it depends on whether you think it’s a good idea to empower a random guy in a beret to become Judge Dredd of Philadelphia.

Cahill, a cat lover who is just as comfortable listening to Garth Brooks and Dolly Parton as he is 80s and 90s hits, leads the Philadelphia chapter of the Guardian Angels. The group started in 1979 in New York City, led by Curtis Sliwa, who later became a talk radio personality and 2021 Republican nominee for NYC mayor. “In the late 1970’s New York City was a modern day equivalent of the Wild West,” Sliwa’s biography states on the group’s website. “Murder and violent crime was the norm. A trip on the subway was an exercise in urban survival. Residents of the city resigned themselves to the reality as the politicians and police seemed powerless.” It’s true that crime was extraordinarily high in American cities in the 1970s and 80s. Today, crime is about half of what it was in 1990, in fact.

To combat the scourge of violence back then, Sliwa donned a red beret and enlisted the help of everyday men and women to engage in what could best be described as performative acts of vigilantism.

Today, Cahill says that each chapter of the Guardian Angels, found across more than 130 U.S. cities and in 13 countries, has the same mission. For his part, Cahill says he answers “straight” to Sliwa. “In NYC, we have many patrol chapters all over the five boroughs,” he adds, explaining that he is also a member of the group in New York and that “hard work, determination, and dedication earned me the right to start a patrol in Philadelphia, my home city.”

He says that there are six Guardian Angels in Philadelphia but that he’s “always recruiting.” The group formed again earlier this year after a long hiatus.

Feeding the homeless but confiscating their items and harassing them, too.

His enthusiasm for the group is clear as is Cahill’s admiration for Sliwa. He earnestly talks about the effect crime has on communities, too.

“If we see someone that needs help, we help them. If we see a crime happening, we stop it,” he then pivots to the softer, gentler community outreach. “Many times, we feed homeless people. We buy some of them clothes and sneakers. If we see needles on the ground, we pick them up so people don’t get hurt. We interact with a lot of people.”

On the group’s Facebook page, you can see a record of some of these interactions. They aren’t all positive.

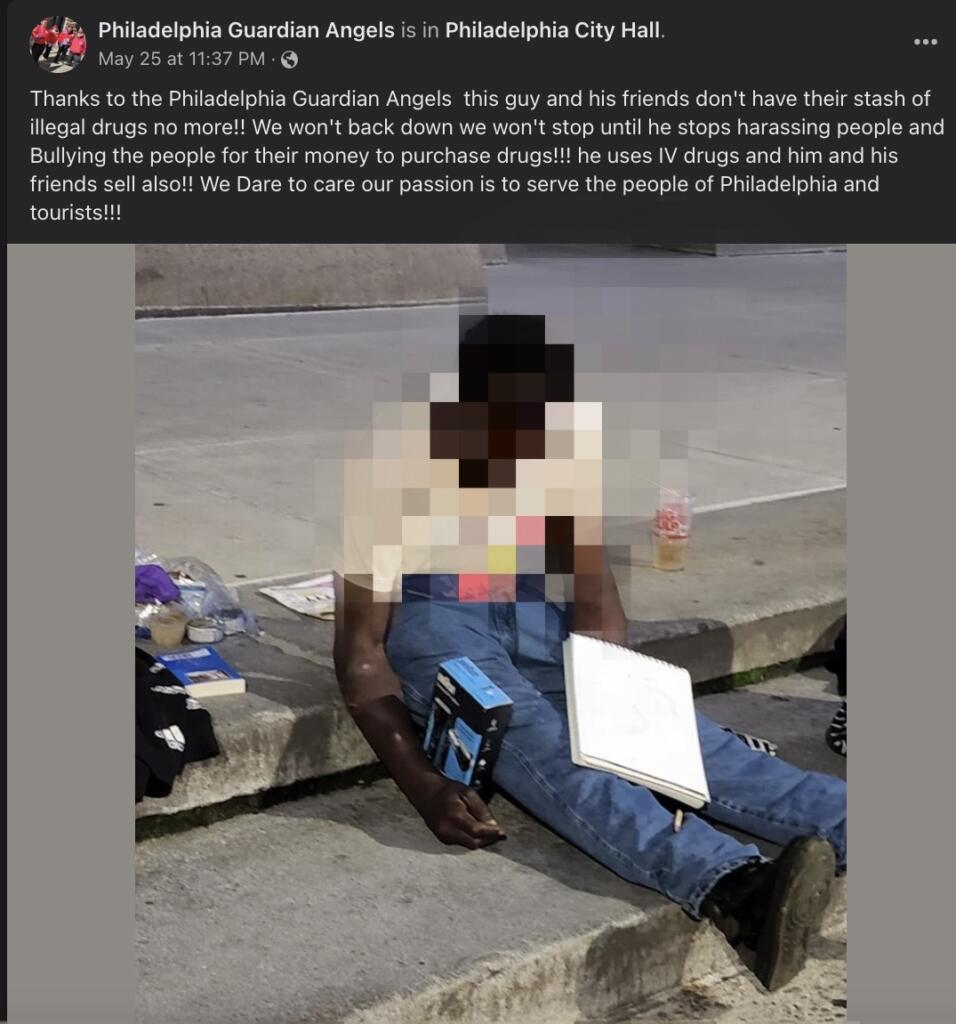

Given that it appears none of these individuals enjoyed due process under law to establish they were guilty of anything and some of Cahill’s claim about their behavior would be defamatory if not true, Philly Weekly is protecting their identity. In one from May 25, Cahill posts a picture of man sitting on the steps outside City Hall with belongings strewn about him. “Thanks to the Philadelphia Guardian Angels this guy and his friends don’t have their stash of illegal drugs no more,” Cahill writes. “We won’t back down, we won’t stop until he stops harassing people and bullying the people for their money to purchase drugs! He uses IV drugs and him and his friends sell also!”

As best as we can tell, no other evidence exists that any of this is true beyond Cahill’s personal investigative conclusions. When I asked him how he determines who is homeless and who is addicted, he demurred.

Commenters, many from the South Silly neighborhood Facebook group, descended on that post and harangued Cahill.

“Stop being vigilantes and actually help people,” one writes.

“You’re a gang of thugs bullying people who need help. An embarrassment to the city,” laments another.

One commenter challenged Cahill to reconsider subjects of his posts.

“Why don’t you go to the corners where the boys are trapping that dope and making the neighbors uncomfortable and take pics of that shit and tell us the good shit you’re doing there,” the commenter retorts. “You ain’t gonna do that though, it’s easier to just fuck with the broken.”

That commenter signs off with “grow some balls.”

In another post from May 24, Cahill claims that his group “took a lot of drugs off the Street tonight” with pictures of his compatriots in Dilworth Park and at least one picture of a small plastic baggie with a white crystalline substance in it. “Addicts there are harassing people making them give them money,” he explains in the post.

To be clear, no law criminalizes homelessness or substance use disorder. The First Amendment also guarantees people’s right to speech, including by way of panhandling.

It’s important to note also that the term Cahill lobs out with unnervingly liberal frequency, “addict,” let alone the conflation of addiction with dangerous criminality, is now considered stigmatic, or in some cases even a slur, and has mostly gone away from the media and social services lexicon.

Of course, the irony to all this is that it would appear Cahill himself could be guilty of receiving stolen property, theft, and even robbery as a result of some of his posts. When questioned about this, Cahill has a response ready.

“People are posting lies about me,” he says. “I never one time went into anyone’s pockets and took out of their pocket. I never one time made them take stuff out of their pockets ever! The drugs were on the ground in plain sight out in the open,” he argues. “These people were harassing women, children, and senior citizens. They were scaring them into giving them money by bullying them, intimidating them, and other things they did.”

Again, no evidence seems to exist that any of that is true beyond Cahill’s word. The pictures hardly convey this claim, too, instead showing mostly people who seem tired, hot, or otherwise vulnerable sitting on the sidewalk or exiting subway stations. Whether any are homeless is also unknown and just a conclusion Cahill and others are making.

“I made them get up and leave and I would not let them pick up their big stash of drugs off the ground. They were using these drugs out in the open in Dilworth Park,” he says, “They were using drugs out in the open…as women and children and seniors had to walk by and watch them get high. This is the facts! I made them leave the drugs behind by not letting them pick them up.” As though he suddenly remembered something, he adds, “These homeless addicts are committing felonies by possessing a large amount of drugs. They are committing crimes by using drugs in public!”

In reality, it is not against any law to use drugs. It is against the law to possess drugs or distribute them or, in many cases, manufacture them, however. Whether these confiscations even involved illegal narcotics is not an established fact, though, and is now unknowable.

“If we see crime happening, we stop it, detain people under citizens arrest, and then call 911 to pick them up from us,” Cahill goes on. “We offer to take these people to detox and rehab. They always decline, say they won’t accept my help. I try to help them. They aren’t willing or ready to get sober. [It’s] sad but true.”

Police distance themselves, condemn vigilantism

As to process, the Guardian Angels do not follow the same evidentiary protocols – painstaking processes created through experience over decades – police do so that suspected illegal drugs are confirmed as such. The Guardian Angels also have no real legal power, though the group insists it does under this hazy principle of “citizens arrest.”

In fact, whether or not their work is sanctioned or encouraged in any way by police is disputed – by police themselves.

“Local PD are fully aware where we are patrolling,” Cahill insists to me, “and they like what we do. Many of them thank me all the time!” Of the May 25 incident, Cahill claims he alerted officers at the 9th District, telling them the group confiscated drugs which he says he destroyed “in a safe manner. No people will die of their deadly fentanyl they had.” When pressed, Cahill says officers have advised him to flush drugs down the toilet or just throw in a public dumpster, actions he says he’s taken.

No evidence exists that what Cahill claims he confiscated was fentanyl. In addition, transdermal absorption of fentanyl, the idea that touching it briefly can get people high or sick, is an urban legend. Instances of officers or others getting sick from touching it briefly are likely a case of mass hysteria brought on by the popular legend as it is quite literally scientifically impossible under those conditions. Of the “confiscation” and “safe” destruction of the drugs, the police “said I did a good job,” Cahill swears.

Police disagree.

“The PPD doesn’t condone, promote, or encourage vigilantism in any form,” counters Philadelphia Police Department spokesperson Sgt. Eric Gripp. “While we support people taking an active role in keeping their communities safe in a number of various ways, the best and safest way to do that is to be a good witness.” Gripp adds that people should report illegal activity to police by calling 911 or, in situations that aren’t emergencies, to let cops know about ongoing criminal activity or nuisance by contacting their local police district directly or the PPD’s anonymous tip line at 215-686-TIPS.

Gripp is quick to point out that police directives regarding the safe handling of suspected illegal drugs and their storage and disposal wouldn’t follow Cahill’s more ad hoc, improvised process of the toilet and dumpster.

No clear power of citizens arrest but dangers abound

Whether Cahill and the Guardian Angels even have the legal right to do what they’re doing in general isn’t clear, either, actually.

Reporting for CNN, AJ Willingham analyzed the concept of citizens arrest through the lens of the horrific lynching of Ahmaud Arbery, a jogger and Black man chased down by three white men in Georgia. The men, subsequently all convicted of murder, claimed the power of citizens arrest as to why they could chase and try to detain, and eventually shotgun down, Arbery.

“Different laws – whether in state codes, precedents set by state court rulings, or some other common legal understanding – sometimes mention use of force, as in New York state, where non-deadly use of force is specifically allowed,” Willingham explains. It also varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction “whether the law can be used for felony or misdemeanor crimes. Some also specify whether someone had to witness the crime actually being committed in order to pursue an arrest.”

In Pennsylvania, the law and court rulings have consistently defined the citizens arrest power as an exceedingly narrow one. Focusing on a specific set of conditions, the concept seems sanctioned in two instances, primarily: if law enforcement asks a private citizen to help with an investigation or arrest; or, if a private citizen is witness to a felony. On record cooperation with law enforcement is, it seems, key to legitimate exercise of a citizens arrest, too.

In 1983, the Pennsylvania state Supreme Court explained in Commonwealth v. Corley that “one making a citizen’s arrest is, definitionally, acting under the authority of the state. The legitimating factor which distinguishes his actions from an unprivileged battery or kidnapping is the state recognition and sanction of this act.” The court adds that “the very occurrence of the act is freighted with the authority of the state.” In other words, a legitimate use of citizens’ arrest, at a minimum, enjoys the endorsement and follow-through by actual law enforcement authorities, the “state recognition and sanction.”

In the absence of that, it appears to be, plainly, a crime in and of itself, what the court refers to as “unprivileged battery or kidnapping.”

Criminal or crime fighter? Hero or fool?

Cahill insists that the “haters” posting “lies” about him online have got him all wrong.

“We always feed homeless people every time we’re out. We feed drug addicts, no matter how they are and what they do,” he insists. “We give them food, soda, water, and snacks. I’ve bought sneakers and clothes many times for the homeless.” He shows pictures of his donations.

It’s a view of Cahill that many didn’t see amid the other, frankly disturbing stuff. Still, it’s a valid question whether or not Philadelphia is served better by the Guardian Angels or by people just feeding the homeless.

And while crime is in fact on the rise nationally, whether this justifies a 1979 approach when crime is still about half of what it was then is also unclear. Hasn’t society evolved from the days of “Popeye” Doyle and “The French Connection?” And if you fight crime by possibly engaging in crimes yourself, does this justify it?

More to the point: At the end of the day, is this courageous community engagement or just foolish bullying?

“Directly confronting individuals by ‘confiscating’ property is not supported by the Police Department,” warns the PPD’s Gripp, “and could not only be dangerous for the private citizen but could also potentially be a crime in and of itself.”