On October 21 at 7 pm. at South Philly’s 2300 Arena, J Russell Peltz will do what he’s done for 50-plus years: He’ll talk boxing, extensively and in painful, glorious, pulpy, statistical, fiduciary detail, just as he did in his first book, the newly-published “Thirty Dollars and a Cut Eye.” He’ll screen some of his most memorable Philly-area fights that he’s promoted since 1969. He’ll heartily welcome fellow fight enthusiasts, boxers old and young, trainers, corner men, and cut men with whom he’s worked throughout the past five decades and pore over the minutiae of the 1,000-plus boxing events he has promoted, honestly (a true rarity in the fights biz) – including over 40 world championship fights – all while recalling each-and-every detail: “Every round, every conversation, every travesty, and every scandal,” Peltz writes.

Ray Didinger, this city’s beloved and preeminent sports writer and multimedia commentator currently hosting at 94WIP Sports Radio and analyzing football for NBC Sports Philadelphia, is celebrating his own golden anniversary in the game (with the recently-published “Finished Business: My Fifty Years of Headlines, Heroes, and Heartache”), and has been friends with Peltz since they were at Temple University starting in 1964. “Freshmen together, and journalism students together since day one, even down to being with the daily Temple News,” says Didinger. “I was sports editor one year, he the next, and became good friends ever since…. He was so passionate and knowledgeable about boxing. I can remember going to J Russell’s house in Lower Merion. The first thing he showed me was this archive, his library of scrapbooks, magazines, old films and VHS tapes of fights from over the years. I know he’s viewed each one repeatedly. And he knows where each tape is, where each punch lands, and loves nothing more than pulling out a Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott film and watching it for the 20th time. That’s when I realized that J Russell isn’t just a fan. He’s living this thing.”

Peltz agrees that he, his mind’s eye and his level of total recall are invaluable encyclopedic tools. Not only as a boxing promoter, but as a writer.

“The book has it all,” says Peltz from his eponymous-titled boxing promotions office near Eastern State Penitentiary on Brown Street. Peltz’s voice is calm, collected and soothing, not the sort you would expect to set up boxing matches and hawk men beating their brains out. “It’s all about the facts, the figures, the finances. I saved every contract, every profit-and-loss statement, every video, poster and program. Nothing was off limits. When I spoke with over 30 of the men who boxed for me, some of them had nice things to say – others, not so much. Some told me they wish they had stayed with me. Others said that I didn’t do right by them. That if I had been more about fighters than fights, I would have been a better promoter. Either way good and bad, it’s all in there.”

It’s true. J Russell Peltz can take a punch, even if it is just metaphorically.

“Look, for most of the century, boxing was among the three major sports – boxing, baseball and horse racing, and Philly was at the forefront of all of them. Books like mine have never been written, as boxing books are just about who-hit-who. Nobody ever went behind the scenes as to how those fights came about, a real insider’s history of boxing in Philadelphia. It was an amazing era for sports, especially boxing, in this city.”

The Weekly’s, however, isn’t just a story about a book, no matter how bloody or absolute, no matter how deep in the weeds Peltz had to get into local politics and sports politics. It’s a story about a life of punches to the face and the labanza, of what it means to stand toe-to-toe, alone, mano et mano, with another fighter for survival – and be the guy behind the guy that makes it happen, even when the sport goes in-and-out of fashion. And, OK, there will be blood, too.

An era. That’s how Peltz and I start this conversation – with 50 years of boxing’s dominance as something past. Because he calls the Philly boxing era a “was,” tells me that Peltz (like so many of us) knows that the sport has lost its luster on a national level, as well as a local level.

“You mean, ‘why has it faded… disappeared, become a niche sport,’” he laughs. “Hey, boxing is not what it used to be, and never will be again. The proliferation of world champions is a huge problem. Say, there were no playoffs in baseball this year. Each champion of every different division would walk around claiming that they were the champs. You’d never know who ‘the best’ was because they didn’t play each other – that’s what happened to boxing. The best fighters don’t fight each other. That’s the number one reason that boxing has receded from the national picture. The death of newspapers hurt boxing, too. There were several editions where sports fans were dedicated to reading about baseball or football as it happened – and of course they saw boxing results too, which were plentiful. When the dailies died, fans of each sport go to their respective websites now – there’s no crossover. There’s a whole generation of sports editors in their 30s who have no idea of the history of boxing, how big this city was, or how to write about it.… When I was a kid, I could name all of the lightweight champions backwards – from Carlos Ortiz in 1961 to Benny Leonard in 1919. I can’t even tell you who the top three are today, and I’m a historian. All I cared about, coming up, is the Gillette Friday Night Fights. Plus, 95 percent of the money in boxing is being generated by 5 percent of the people boxing now. When I see boxing today, it is not the sport I fell in love with. Now, it’s a money grab, two guys playing chess and moving the rooks around, not about who is the best, but rather who can make the most money with the least risk.”

So, there’s that.

Peltz makes note of a Floyd Mayweather or an Anthony Joshua making millions per fight. But, boxing’s middle class – just like in the everyday class wars – is dead. “Everybody wants to be undefeated and waits to fight in a pay-per-view show. In the days when there was only one champion in each division of eight divisions, the only way to get up was to beat the guy ahead of him, and ahead of him, and ahead of him. Now, there’s four champions in each of 17 weight classes. There are now five weight classes between 106 to 115 pounds. Why not just have a title for every pound on the scale? Besides, no one wants to broadcast fights unless they’re title fights or the boxers are undefeated?”

Peltz’s take-away from all this, currently, is that no one cares about boxing’s fans – being fair with ticket prices and putting together exciting, daring matches that were prevalent in the past; something for which he is renowned and beloved. “No one was a matchmaker on the level of J Russell,” says Joe Hand Jr., the son of Joe Hand Sr. and the president of the self-named, family-run Philly promotions company started in 1971.

Peltz hasn’t taken out a promoter’s license in two years, and isn’t actively running his own fights, at present – instead opting to consult and advise on fights, fighters and matches (Joe Hand Promotions uses J Russell’s services, for example, as does Michelle Rosado’s Raging Babe Promotions), along with managing “a few kids because I’m trying to help them,” he says.

“They kept me out there, pumped up and hustling,” says Peltz of Rosado and Hand Jr. “Right now, I’m helping Joe Hand with his upcoming matches at Live! Casino in November (the debut boxing event at the intimate 1,200-seat hall on Nov. 18 starring South Philly’s homegrown heavyweight phenomena, Sonny Conto). With boxing venues few-and-far-between, Hand. Jr. is thrilled to be part of South Philly’s sports complex’s newest venture.

“Ever since the Blue Horizon closed, the city’s boxing enthusiasts, all of its players, have been looking for something to replace it,” notes Hand Jr. “While nothing can ever take its place, we’re certainly excited about newer venues like the 2300 Arena, Parx Casino and now, Live! – all special.” With Hand Promotions’ core business being close circuit TV events and selling pay-per-view screenings to bars and restaurants, and the Cordish Company being hands on when its Live! was being built, Hands, Sr. and Jr., became an instant part of the casino’s entertainment plans.

As entertainment and Peltz go hand-in-hand, Hand Jr. says that whenever his company does a show, he asks that “Russell, if he is so inclined, does the matchmaking. If there is one thing that I have learned from seeing thousands of fights in my time, there is – beyond a doubt – nothing like a J Russell Peltz-made show. His matches are terrific. He’s been helping me, personally, since we started doing Parx, always gracious.”

The daily grind of boxing promotion – that’s over for Peltz. “I’ve been consumed by writing the book. It’s been my whole life since COVID started, which was fortunate only because the pandemic followed right after my 50thanniversary show. The stress of getting called on Tuesday for a Friday night main event because he got cut, or he disappeared, or he doesn’t want to fight this other guy because he’s too tall, because he needs to be in the blue, and not the red corner, or because he doesn’t want to fight a guy on somebody else’s turf – I don’t miss the scramble.”

Peltz jokes about how the Whiz Kid-era Phillies had a manager, Eddie Sawyer, who came back to the team in 1960-61, but quit after opening day. When asked why he got out of the game by a local sportswriter, Sawyer said that he was 49 years old and wanted to live to see 50. “I say to you that I’m 74 and want to live to see 75,” laughs Peltz. “Let someone else have a turn at such aggravation.” Besides, Peltz just got back some of the first reviews of “Thirty Dollars and a Cut Eye,” and was told, by one scribe, that he was a better writer than a promoter.

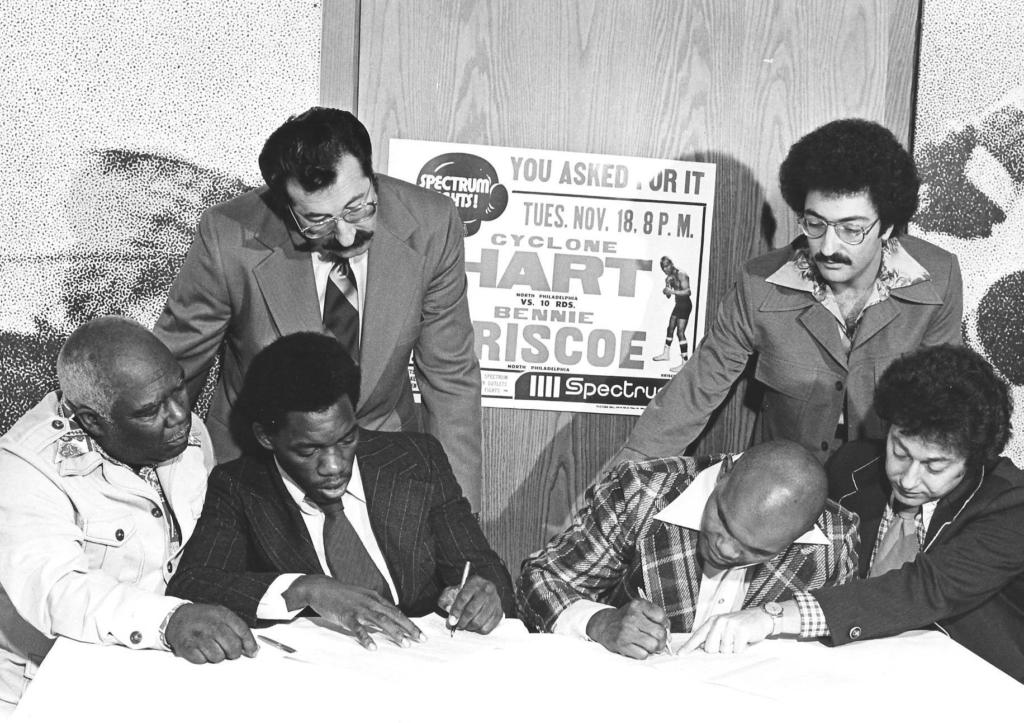

Didinger says the difference that Peltz has made to the sport and the scene of boxing comes down to passion (“He was a great sportswriter and editor, and could’ve been a columnist if he chose”), proximity (Philly’s boxing haven, the Blue Horizon, was right down the street from Temple’s campus on North Broad) and self-determinate destiny. “He always pointed at the Blue Horizon with a ‘there it is,’ and he just knew that he would be there. That was a goal he set for himself, and the year after we graduated – as much as we had laughed about it – there I was, standing in line to get into the Blue Horizon for his first show, Bennie Briscoe vs. Tito Marshall. His name was on the poster outside. And I bought my ticket at the box office from his mother and father who were working the window. Even though we were friends, nobody got comps. ‘It’s a business, Raymond-o,’ he used to tell me.”

What Didinger admired about Peltz was that, in a business where so many want to cut corners (“and game the system”), Russell never did that. “Russell was an honest boxing promoter. Maybe the first. Certainly, the last. He revered the sport. Cherished its history. And, as a promoter, he kept it clean. He ran honest shows. He thought he had ownership of some fighters along the way, he never paved their way to success. If you were going to fight for Russell, his idea was that he was going to make good fights. Russell was a straight shooter, and honest – even if that was something that those who were less honest didn’t want to hear. That’s how he did business”

Boxing is legendary for having owners who had fighters, and would attempt to handpick their opponents with a focus on knowing who their guys could beat, pile up wins, and move up in the rankings, and make money. “Sometimes that has been in a dishonest way,” notes Didinger. “That’s when it is in the interest of the fighter and their management and not, say, the sport.”

For Peltz, his fighters had to earn that. “You had to do that yourself without Russell paving your way. If you were fighting for Russell, whether he had a piece of you or not, you were going to fight good fights,” says Didinger. You had to fight your way there. And Russell took real pride in being a great matchmaker. He’s always been true to making good, entertaining fights. And he’s handled some great fighters, whether it is neighborhood guys all the way up to the Roberto Durans and Tommy Hearns. The best boxing promoter in Philadelphia, ever, was the guy I went to school with.”

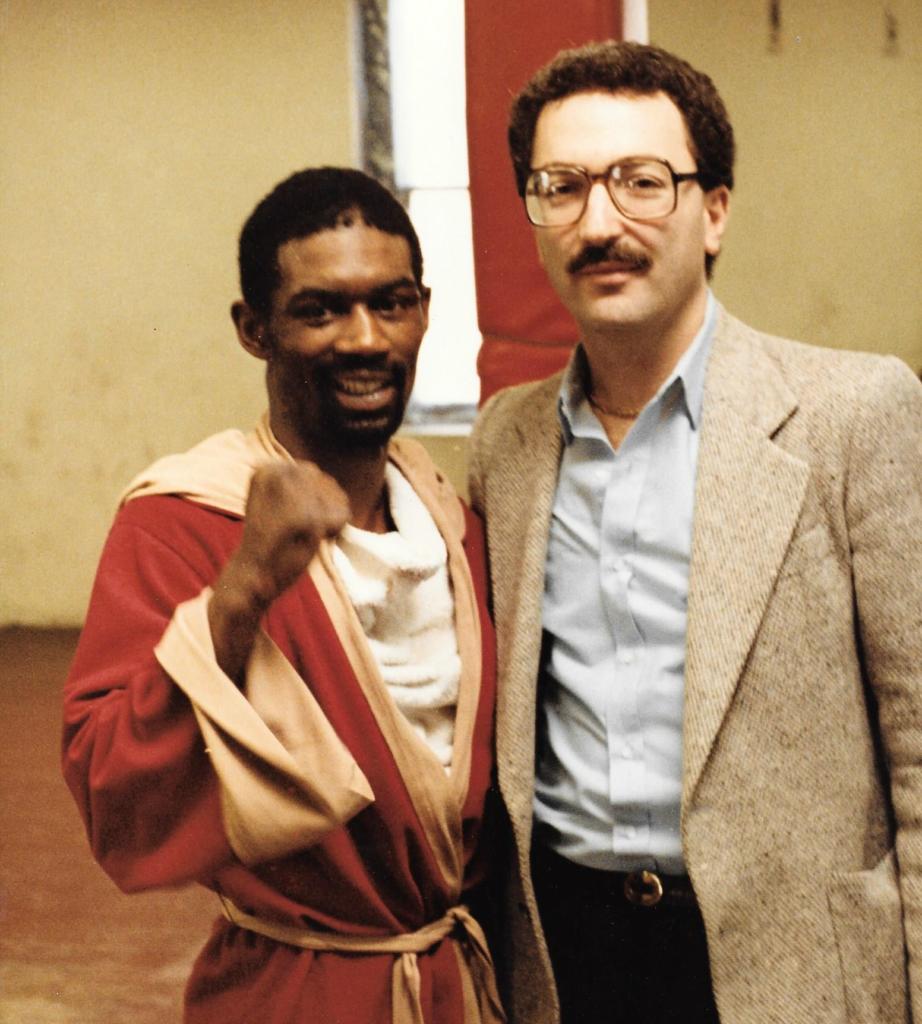

While Peltz’s present is filled with writing and “Thirty Dollars and a Cut Eye,” certain Philly boxers of his past, winning or losing, stick out for the promoter after 1,000-plus fights. But why? What differentiates a bantamweight like Baby Kid Chocolate from a middleweight such as Bennie Briscoe (Peltz’s first fight promotion), from his “hot-and-cold relationship” with junior lightweight Tyrone Everett (especially his still-controversial title battle with Alfredo Escalera) from Marvelous Marvin Hagler, Emile Griffith, Thomas Hearns, Aaron Pryor, or Joltin’ Jeff Chandler?

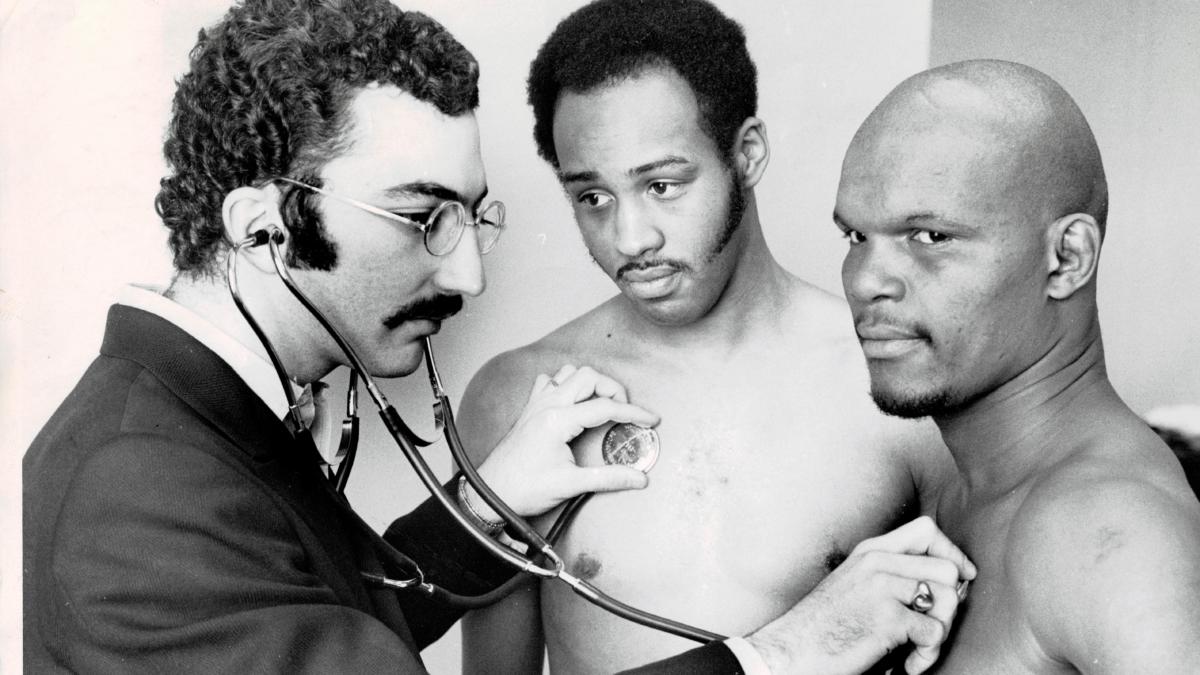

“Well, it wouldn’t be Baby Kid Chocolate,” Peltz says when I bring up the North Philly boxer who battled in Philly’s rings 20 times between 1973 and 1983 with a 19-7 / 8 KO record and a rep as a mini-Joe Frazier. “Bennie Briscoe was my first fight. He put me on the map. You had to be around to watch him fight – I have all the films – he was something. From 1962 to 1982, he had 66 wins, 53 by KO, 24 losses and 5 draws. Briscoe and Hagler fought a 10-round-fight at the Spectrum, no bullshit titles with no TV, and drew 15,000, the largest indoor crowd in Pennsylvania for a non-championship fight.”

Boxing’s most colorful characters at present – like a Gabe Rosado, a great local fighter with a style and personality reminiscent of Philly’s greats – are few and far between, and even pale in comparison to those fighters of the past such as a Foreman, or the eternal showman, Muhammad Ali. Peltz, however, puts this down to the current crop of sportswriters who don’t know how to find, and tell a good story.

“The writers don’t care or can’t imagine that some stories out there could come from people in the fight game,” says Peltz. “Most up-and-coming neighborhood fighters aren’t guys who came up through the colleges where they had to take classes in underwater basket-weaving. C’mon. They come from poor backgrounds – sports’ blue-collar workers – and don’t often have the same thrill as someone playing the main room in Vegas or Madison Square Garden. I’d like to see someone report from small boxing clubs in Corpus Christi, Texas, Ames, Iowa or even smaller local Philly clubs now, and report what it’s like to get hit in the face three, four times a day, then go out, fight for $500 or $700, and support themselves or a family – even having full-time jobs on the side like Bennie Briscoe, who had a rat control business. They all worked after they made it, save for Joe Frazier.”

Besides, there’s a difference – today – between a Philly fighter and a fighter from Philly. Among the fighters in town now, Peltz seems enthusiastic about Boots Ennis, the undefeated local welterweight. “He hasn’t been up against the best, but neither had George Foreman until he fought Joe Frazier,” Peltz says. “Sonny Conto? If he’s handled right, he’ll make more money than Boots Ennis. He’ll be the hottest ticket in the city – an Italian heavyweight from South Philly. You can’t script that better.”

One thing we save for the close of the conversation is the eternal why: why the hell get into boxing promotion in the first place?

For someone such as Joe Hand Sr. and Jr., coming up in the game along with Peltz has helped define what boxing in Philadelphia has looked like since Russell started in 1961 and Joe Sr. commenced his promotions company in 1971. “Look, our families have known each other for 50 years,” says Joe Hand Jr., who, as of Oct. 21, will celebrate 50 years in the business. “Making it a career for myself, and what I see in Russell and my dad, are two guys who absolutely love and respect the business of boxing. They are the greatest ambassadors for this sport. Russell is always thinking about the fans and their experience – and I know my dad is the same. Both of those guys have touched, introduced and-or exposed so many people to boxing in this city, hundreds and thousands of fans, over 50 years. That’s truly an accomplishment.”

For Peltz, it was because boxing was in his blood. Upon that realization in 1967, he did anything and everything in his power to make it happen. “When you’re 22, you’re antsy. I remember my wife – at the time, she wrote for the Inquirer – asked me what made me think I could do that, become a boxing promoter. I told her that we were young, I had $5,000 in the bank, I’ll blow it in six months, and I’ll have a hell-of-a scrapbook to show our kids about the time Dad was a boxing promoter. An independent promoter today can’t do that – take that chance, even with a winner, a legit fighter – without television. Not with their own money. You’d have to kick over half of his contract to ESPN, Fox, DAZN or, to a lesser-extent, DeLaHoya with Golden Boy. It’s a closed shop.”

That Peltz, the promoter, did it all cleanly and fairly – it is his reputation in the boxing biz, and his detail-heavy book’s emotional core. The writer-turned-promoter-turned-writer gets a choke in his throat telling a story about his now-late son, Matthew, at age 14. J Russell had just returned home from the office – the ring – when Matthew Peltz asked his father about why sportswriters wrote terrible things about most boxing promoters, accusing them of stealing fighters’ money, fixing the rankings, and paying off officials and referees. “‘But when they write about you, Dad, it is all good, and cool,’” recalls Peltz. “Money can’t buy that. I think I got a fair shake from the papers, the state athletic commissions, from people who don’t or won’t bend the rules. I’d rather have it that way than open season, and Greg Sirb is – head and shoulders – the finest commissioner we’ve had in my time, and that includes Howard McCall, Zack Clayton, Jimmy Binns, Frank Wildman, George Bochetto. Sirb’s the guy. People call Sirb crazy, but you know what? To be in boxing, period, you have to be crazy.”

With promoters as individual as the boxers themselves, what made or makes Peltz a singular entity within that? What is his signature?

“I was always more about pleasing the fans than protecting the fighters,” he says frankly about loving the fighters, but being deeply and dearly all about the game. “I promoted fights. Not fighters. I came from a time where the best survived. When I was a kid, if you didn’t come in first, second or third in, say a track meet, you didn’t get a medal, and you had to learn to deal with it. Today, everybody’s in the protection business in boxing. You’re betting the corner – you clean up. Everybody gets a gold star. Not everybody is in boxing now because it was in their blood from the time when they were kids. That was me. That’s still me now.”

@ADAMOROSI