It’s the last weekend in September, and opera world giant Lawrence Brownlee – the world-class tenor who, since 2017, holds an additional job as artistic advisor at Opera Philadelphia – is hastily pulling into town and heading to the Wilma Theatre.

“No rest for the weary… I just left Philly for Atlanta, and I’m back again,” said Brownlee, still breathy from his arrival.

At any other time, a turn into the Wilma’s lot would be an odd one, as the singing business of Opera Philadelphia usually takes place on the Academy of Music’s stage, or one of the grand halls in the Kimmel Center. This is the time of COVID-19, however, and all bets are off, with all familiars turned on their head. So, presently Brownlee and a smaller Opera Philadelphia team (than usual) of musicians, engineers and light and sound techs have set up camp across the (Broad) street, crafted its stage like a recording studio – with no audience – and taping several shows. There’s “Lawrence Brownlee & Friends in Philadelphia,” a recital and conversation program where he is joined by sopranos Lindsey Reynolds, Sarah Shafer and Karen Slack, accompanied by pianist Myra Huang.

There is “Cycles of My Being,” a pained-but-proud song cycle about what it means to be a Black man in America, with lyrics from Brownlee and Terrance Hayes, and music by new Philadelphia resident, composer and conductor Tyshawn Sorey. Days later, as I speak with David B. Devan – Opera Philadelphia’s bow-tied general director and president – composer David T. Little’s mournful “Soldier Songs” is having its audio recorded at the Wilma, with its filming dates planned as on-location shoots, outdoors, at the Brandywine Conservancy.

All this talk of filming and recording is due to the treasured – and highly successful – company’s newest experiment in a long line of innovations under Devan’s watch: the Opera Philadelphia Channel. Debuting on Oct. 23, for viewing on laptops, mobile devices, or oversized, home television screens (“that’s what we’re hoping, as our programming is epic,” said Devan) via AppleTV, Android TV, Roku, FireTV, and Chromecast, the Opera Philadelphia Channel reimagines and reinvents the OP’s 2020–2021 Season as a new streaming app with all the bells and whistles you’d normally get from Hulu, Amazon Prime and Netflix.

Fond of the comparison, the analogy between what Devan has done with his previous major innovation – the O Festival, which began with O17 in 2017 – and the concept of new streaming technologies, networks and marketing meant fresh, often freak-a-deaky commissioned works (e.g. a mod opera based on the weird and wooly life and work of Warhol, “Andy : A Popera” co-crafted with the drag-based Bearded Ladies Cabaret), socially and racially relevant pieces (a divisive “We Will Not Be Moved,” tied to Philly MOVE tragedy and touched by elements of hip hop music and choreography), and twisted takes on the classics (a “Mad Men”-like envisioning of “La Traviata”) into 12 days of immersive, repeated, must-see programing. Before the O Fest commenced there were Knight Foundation-sponsored “Random Acts of Culture” at Macy’s Center City and Pat’s Steaks in the Italian Market where opera simply broke out, spontaneously, like car alarms during a tailgate.

Combine all that with a mission – a 2013-commenced rebranding campaign that, has since found Opera Philadelphia reaching out to Philly’s richly diverse racial population and millennials – as opposed to opera’s usual archaic notion of what the classicist form should look or sound like – and a public outreach like never before into what and where opera can occur (co-productions with FringeArts for performances in warehouses, outdoor venues such as Independence National Historical Park and its Opera on the Mall) and Opera Philadelphia isn’t just your usual stuffed shirt, old white guy-based art form anymore.

Opera Philadelphia is all about the 21st century and beyond – culturally, communally, developmentally, historically, racially and progressively.

Even when you are not speaking to him in person, David B. Devan’s style and enthusiasm bound through the line like a McLaren 600LT through a red light. Sartorially dashing and giddy, Devan got to Opera Philadelphia in January 2006, was appointed general director in 2011, and began building partnerships with local arts orgs (the Barnes, the Fringe) and beyond (the Apollo Theater, the Santa Fe Opera) so to preach his directive of progressive opera – all while keeping the local boards and the area blue hairs happy with the traditions of “La boheme,” and its ilk.

An incomplete list of Devan’s commissions and co-commissions include “Charlie Parker’s YARDBIRD,” by Daniel Schnyder and Bridgette Wimberly, starring Brownlee; “Cold Mountain,” based on the novel by Charles Frazier and written by Curtis Institute of Music-based professor of Composition Jennifer Higdon and Gene Scheer; and a gloomily cinematic “Breaking the Waves” by Philly composer Missy Mazzoli and Royce Vavrek, based on the film by Lars von Trier – named the Best New Opera of 2016 by the Music Critics Association of North America. The annual O Festival – which started in 2017 – has been called a towering achievement by no less than the New York Times, and was set to repeat itself, starting this week. That is, until…

“It was like the second week in March 2020 when the whole Opera Philadelphia team circulated, quickly, the decision we made to shut down our office and close all possibilities of ‘Madame Butterfly’ – which was getting ready to open six weeks from that point – and most of the annual fundraising we had planned around the Puccini opera,” said Devan. The OP prince and his marketing team quickly learned through market research across the next several months that, yes, people were missing that which took place in the theater, but were not yet ready to leave their homes even if they could. Many music fans, opera and otherwise, were also beginning to experience camera fatigue, what with every performer Zooming and Facebooking every musical fiber of their being.

“Along the way, we did a brief digital festival of some of our greatest hits, and put the stuff online for free,” noted Devan. “We wanted to give our fans something to watch, but we were also testing to see what they watched most AND what they weren’t watching. That got us to the point of understanding the way forward. We didn’t want to put a BandAid on the pandemic, but, we did seek an opportunity for us to do meaningful work with artists in a heightened way, something could be, in its own right, a great, artistic activity. Gee, maybe we needed to find something we could do in a post-pandemic world too.”

Frank Luzi, the OP’s VP of Marketing & Communications, stated the finances of the company are in good shape, dependent as it has been on fundraising for nearly 80 percent of its revenue and ticket sales for the other 20 percent. “Back in 2015, when we announced Festival O, we embarked on a fundraising campaign to grow the company and start the festival,” he said. “In 2017-2018, the year of our first festival, our budget was about $17.5 million. However, that figure has been reduced in subsequent years to around $12.5 million.

Now, with COVID-19, we’re operating at a very reduced budget of around $8.5 million for 2020-2021 and the Opera Philadelphia Channel season. Support for the company remains strong from individual donors and foundations, though we continue to look for increased corporate support. We’ve had to be nimble to respond to the market, and that is especially true now with the uncertainties in the market due to COVID. We are working to conserve cash, employ our artists safely, and be in a position to return to theaters as financially healthy as possible.”

Devan and his team conceived of the Opera Philadelphia Channel between June and July, with the real work of converting an entire company into “an HBO within four weeks,” starting as soon as the I’s were dotted and the T’s crossed.

Remind Devan that he once told this very writer that his goal with the O Festival was to create a “Netflix-ification of opera,” and he laughs. “Be very careful what you wish for,” he said regarding the current daily business of his OP filming operas in hastily built studio settings, pushing people into editing suites to splice and dice digitally and creating software to make his Opera Philadelphia Channel look and sound just like Amazon Prime or Netflix. Taking that look and feel further is the fact that when the Opera Philadelphia Channel launches on Oct. 23, to represent the company’s 2020/2021 season, it will use OTT – Over the Top state-of-the-art software – which is the same technology platform that drives the Netflix engine. “Oy, right?” Devan said, feigning exhausted exhilaration.

That Devan & Co found a (brave) new world solution to a (bold) old world performance genre to his partners in crime – David Levy, Opera Philadelphia’s vice president of Artistic Operations; Rachel McCausland, OP VP of Development; and Frank Luzi, the vice president of Marketing and Communications. It was an especially sweet sound of music to the ears of Opera Philadelphia Music Director Corrado Rovaris and the OP’s recently anointed artistic advisor, Lawrence Brownlee.

“Corrado was way onboard and really leaned into the idea of the channel,” said Devan, remarking that – as we spoke – the maestro was conducting the “Soldier Songs” score on the makeshift studio stages of the Wilma. “Corrado really bought into the idea that, because of safety protocols of COVID, that there must be opportunities to do singular, nuanced, individual work.”

So, yes, Rovaris is happy with the Opera Philadelphia Channel, how it is moving forward, and busying himself in the present with recordings across Broad Street. At the same, he and Devan are having all sorts of dialog about how they want their orchestra and vocal chorus to come back together, in parallel with making and maintaining their channel.

“Corrado has straddled those two worlds,” said Devan, considering the best- and worst-case scenarios. “We are being practical. We know that the droplet count and the safety distance for singers is 15 feet, opera singers even more. That’s really far. We know that wind instruments’ droplet count and safety distance are less than 15 feet, but more than six feet, so we are looking at how to be able to employ our orchestra and our chorus. We are looking at our civic life on the other side of this. We are looking at different ways of doing opera with smaller ensembles. We are doing things just like we did last night, outdoors, at Dilworth Plaza.”

Despite the safety distances that Opera Philadelphia must pursue, they must also uphold the honor and the fact of being stewards of an artistic community and an ancient musical heritage, no matter how experimental they might get. “We need to, with this enemy, figure a way to work with our artistic community – the channel is a start – a way to communicate until we can literally be inside theaters again. Then rethink that too. Hopefully we can unleash a great amount of artistry together.”

Talking about the Opera Philadelphia Channel’s initial offerings, Devan mentioned how one-time OP composer-in-residence David T. Little’s “Soldier Songs” was a perfect pandemic film choice: an elegiac yet triumphant piece for seven instrumnetalists and one singer (“we can on have 25 people in our studio, including camera people, technicians and artists”) about a war veteran who lives in a camper.

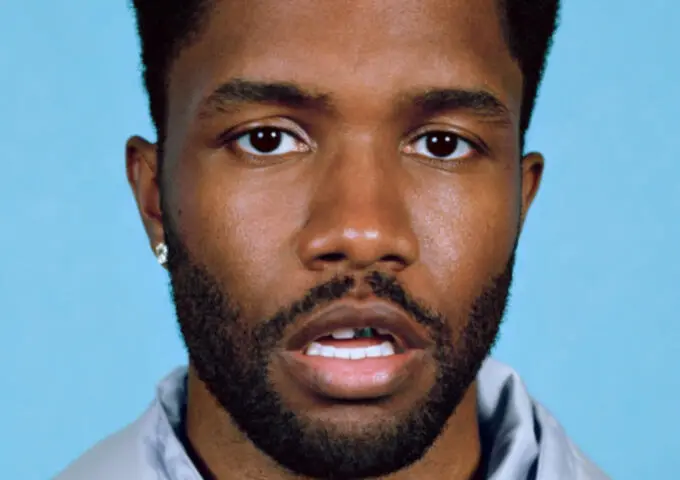

“We need to see diversity in every aspect of the company: the boardroom, backstage, in the administrative offices, in the orchestra and the chorus.”

Lawrence Brownlee, artistic advisor, Opera Philadelphia

“We actually bought a camper and are filming this in the old-fashioned way, building a new set and crafting it as if we were making a movie – NO – we are literally filming a movie,” Devan said of the intimately-lensed production starring Johnathan McCullough, a baritone who’ll also man a camera and co-direct with James Darrah, the director behind OP’s visionary 2019 production of “Semele.” Bringing in soprano Lisette Oropesa to discuss her star-making turn Violetta in OP’s 2015 take on “La traviata,” after screening that 5-year-old “debut of the decade,” is a coup for Devan’s burgeoning television channel. “We’re making this up as we go along,” saud Devan with a giggle. “What was once solely available to 515 people at the Kimmel’s Perelman is now available internationally.”

Bass-baritone Sir Willard White makes his long-awaited Opera Philadelphia debut in “El Cimarrón,” composer Hans Werner Henze’s drama about a real-life Cuban activist who escaped bondage on a sugar plantation, survived in the jungle, fought for Cuban independence from Spain, and lived to describe it before dying at the age of 113. “We’re doing that with Sir Willard, three musicians and tons of percussion,” said Devan of C-19 ecomony of space. “We’re hoping that all artists of color will be able to relate to, and reflect upon, this experience.”

Known for his color-blind casting practices (“That was a large part of what drove me to Opera Philadelphia,” said Brownlee), Devan and Opera Philadelphia has been dedicated to Black causes and matters of social justice since his start there.

“We need to see diversity in every aspect of the company: the boardroom, backstage, in the administrative offices, in the orchestra and the chorus,” said Brownlee. “We need that if we are to truly market to different neighborhoods and audiences. Each area and each audience needs different language, certain awareness, true diversity.”

There’s 2017’s “We Shall Not be Moved,” an interdisciplinary chamber opera by composer Daniel Bernard Roumain, librettist Marc Bamuthi Joseph, and director-choreographer Bill T. Jones about North Philly teens discovering the West Philly house and history behind the MOVE organization, and its deadly 1985 standoff with local police.

“The MOVE show was perfect in that it showed audiences that opera is not this stuffy thing,” stated Brownlee. “It helped to open eyes and whet appetites as to what new can be done AND started a conversation about race in Philadelphia.”

2015’s “Charlie Parker’s YARDBIRD,” with music by Daniel Schnyder, libretto by Bridgette A. Wimberly and a career-refining performance by Brownlee, was equally dynamic in opera’s discussion of race. Both of these shows were among the finest examples of how art interprets the Black voice – the cultural Black voice and the political Black voice.

“It is the voice of America,” noted Devan. “As a white leader of an arts organization, I don’t have a black voice agenda other than that we give people in our artistic community – all of its people – a voice; a way to tell their stories. All we do is produce what they want to tell. ‘We Shall Not Be Moved’ is an important story. It wasn’t our work. It was their work. We just gave it a good home.”

The same historicity and import were instrumental when getting one of America’s premier Black opera singers – “Larry” to Devan – to make his debut with Opera Philadelphia as the brooding, buoyant Charlie Parker in an opera written for him. “Corrado was crucial in bringing Brownlee to the company as they had worked together at la Scala,” stated Devan. “He was famous for his bel canto work and the standard canon of Rossini and all that Italian work when we asked him If he would be interested in us writing an opera for him. I mean, WHAAAAAAAAAT?”

Devan goes on about bringing Brownlee into Opera Philadelphia as its artistic advisor, a role that finds the tenor dealing with Black civic and cultural leaders for the reasons of community outreach and development necessary for the future, as well as artists. “We created the artistic advisory position for him to really bring his viewpoints of a Black man living in America to our practices so that we could start some truly thought inclusion work. He’s working to make sure that we hear all the artists who can sing these roles and other artists of color who get missed in the machinery of a largely white opera industry. Plus, Larry introduced us to Tyshawn Sorey, our new composer-in-residence who, quite actually, is the bomb.”

Brownlee picked up the story to discuss how a complex composer, a Black modern classicist who had never written an opera, became that Opera Philadelphia composer-in-residence (with an even newer gig, as a professor of music gig at University of Pennsylvania to follow). “‘Cycles of My Being’ is very progressive – there is a strong Black Lives Matter element to it – and is being captured in this raw, but highly cinematic fashion,” said Brownlee. “Tyshawn is very focused on making the music right… flexible… it is an extremely difficult piece.”

Brownlee has made singing difficult music something of a calling card since performing as Charlie Parker in “YARDBIRD.”

Known abroad with a successful career of bel canto music, “YARDBIRD” was a delicious challenge for Brownlee, dramatically and musically. “It showed that I had a lot of range as a singer, as an actor, and as a musician; that I could use my voice in many different ways,” said the tenor. “Suddenly I wasn’t a one-trick-pony anymore.” Doing “YARDBIRD,” especially on the stages of the Apollo where so many Black singers and musicians made their bones and won the reputations, was an earth-shattering, soul-stirring invocation of what it meant to be an artist of color in America. “It was, as if, I had the ghosts of so many giants on my shoulders,” said Brownlee. “Everything about ‘YARDBIRD’ was a game-changer for me. A showcase such as ‘Lawrence Brownlee & Friends’ that I’m doing for the Opera Philadelphia Channel will be fun – me and several women with deep ties to Philadelphia (sopranos Lindsey Reynolds, Sarah Shafer and Karen Slack, accompanied by pianist Myra Huang) performing the work of female composers (Clara Schumann, Nadia Boulanger, Amy Beach, and Jacqueline Hairston). But works such as ‘YARDBIRD’ and ‘Cycle of My Being” test my metal.”

So what does it mean to Brownlee to be a Black man in opera in 2020? Not just Opera Philadelphia, but the whole of a form sadly unrepresented by additional artists of color?

“That’s a big question,” he said, holding back a chuckle. “Wow, I feel like, yes, I’m representing Black men in opera and in the arts. But we’re currently seeing some of the disparity and the opportunities that we, as Black people, are given compared to other people. It wouldn’t be fair if I didn’t say that I had been given the fortune of having some great opportunities. I know though that I am probably the exception and not the norm. I look at my Black colleagues, and others who have struggled who are incredibly talented, and the advances they have made recently. Look at last year’s ‘Porgy & Bess’ at the Metropolitan Opera (at the Met for the first time in nearly 30 years). That stage was littered with talent. All of the world’s great stages should have these sorts of opportunities for Black people. Sadly, few of them do and are.”

Philadelphia is progressive in that way in that it gave the world contralto singer Marian Anderson – the Met’s first Black soloist. Opera Philadelphia is progressive in that way, by Brownlee’s account, and he believes that local audiences – and the world, if the Opera Philadelphia Channel has its way – will commence to seeing more of the Black artist initiatives (on stage and off) that he and Devan have been pushing for, soon after this pandemic gets done with and the Opera Philadelphia company can forge its new paths, onstage and online.

“What does it mean to be a Black man in opera in 2020?” asked Brownlee. “It means we’re still fighting the good fight that was started by George Shirley (the first African-American tenor to perform a leading role at the Met) and Camilla Williams and their like. I encourage all Black artists to stay focused and on track – stay with their noses to the grindstone so that they could make progress. We see a lot of social issues happening right now. And I hope that there is a seismic shift because of it all.”