“I think the reason vampire movies have been so popular over time is that they share so many parallels with human beings” — Alexandra Cassavetes

“Over the years all these vampire movies have come out and nobody looks like a vampire anymore” — Johnny Depp

This year’s 125th anniversary of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” signals many things to many audiences. Along with the public’s consciousness and willingness to succumb – literally and figuratively – to blood lust, and all things remotely Gothic (see this space soon for my David J from Bauhaus interview about this very thing), the need to feed, beyond the Halloween holiday is tied to sexuality, homoeroticism and medical issues such as that of tuberculosis in the 19th Century leading to post-mortem identifications of ordinary citizens as vampires.

HBO Max’s Irma Vep, the AMC Network’s re-do of Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire, the soon-to-be-released Renfield starring Nicolas Cage as Dracula, the upcoming production of Nosferatu, and a YA reboot of True Blood: the vampire as a cultural touchstone never dies – why?

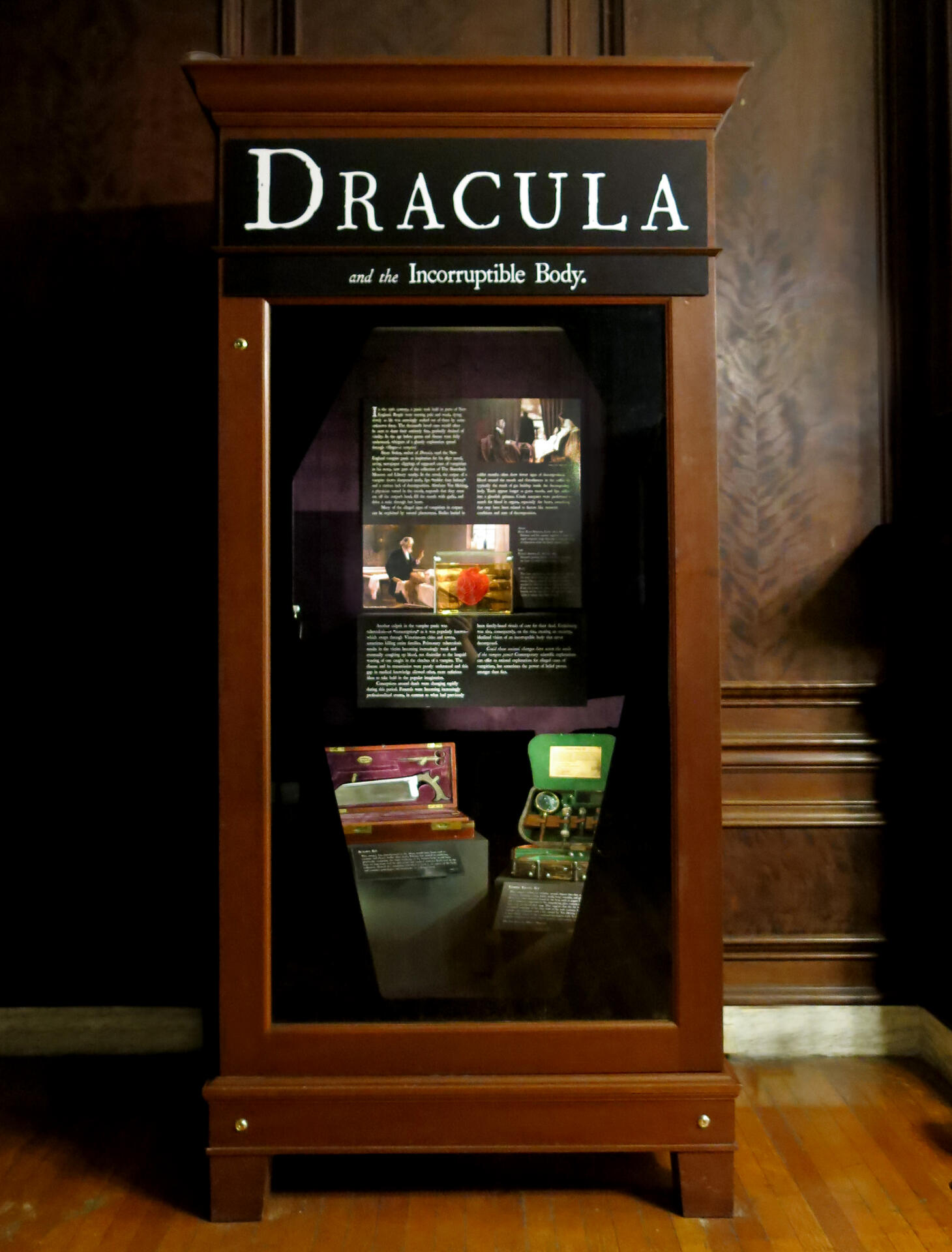

Speaking with curators at the Mütter – the world-famous medical museum dedicated to anatomical and pathological specimens, wax models, and antique medical equipment donated by Dr. Thomas Dent Mutter in 1858, and a spiritual home to filmmakers such as David Lynch and the Quay Brothers of Through the Weeping Glass fame – in time for its 365-day long celebration, The “Year of Dracula,” the dissection of myth becomes something of a more physicalized deconstruction.

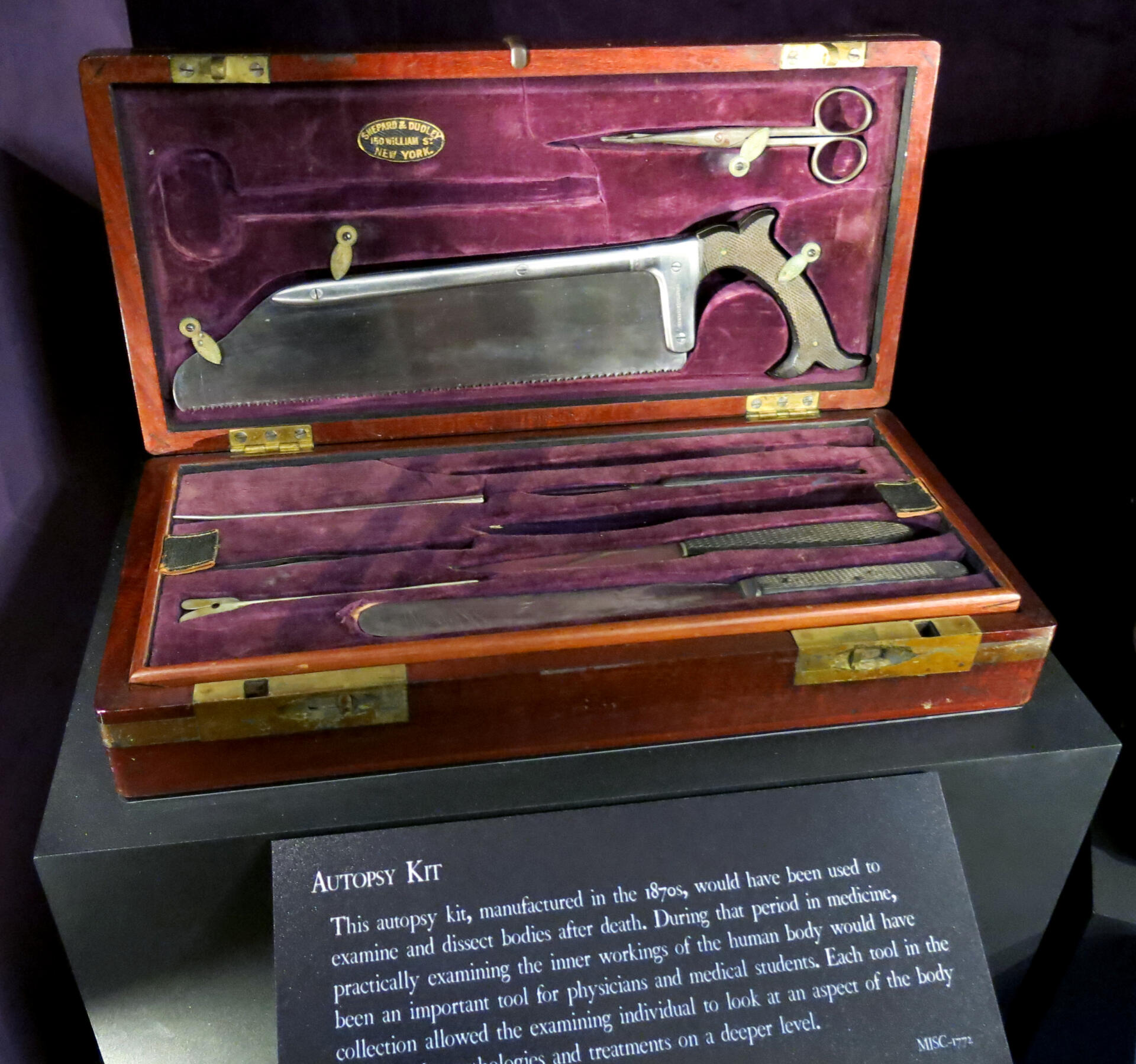

The Mütter Museum and its Dracula and the Incorruptible Body case exhibit, for instance, features a large blacked-out glass front in the shape of a coffin, and autopsy kit with rib shears, skull chisel, and dissecting scalpel, a glowing vermillion heart and a vampire killing kit with a gun, ivory Crucifix, glass vials, and bullet molds – some antique, some contemporary.

Old, new, bloody and blue, Dracula reigns supreme, again.

For an expert opinion on all things vampire, I spoke with Meredith Sellers, the Mütter Museum’s Arts & Accessibility Programs Coordinator and one of the exhibit curators for Year of Dracula.

A.D. Amorosi: The 125th anniversary of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” – how does the novel speak to audiences in 2022, pop culturally and beyond?

Meredith Sellers: We are in an interesting moment, emerging slowly from a global pandemic. Horror is a way that many of us use to process traumas or fears through metaphorical means and I think it is particularly apt in this moment. The figure of the vampire speaks to fears around death and disease. As we explore in our case exhibit, the misunderstanding of disease and a distrust of science led to Vampire panics like the one in New England in the 1800s. Disease and mass death tends to breed panic and misinformation, no matter what era you’re talking about or how enlightened people might believe themselves to be. Dracula itself is an incredible melding of the new world and the old, wherein the protagonists are using cutting-edge technology like audio journals and typewriters, but they are ultimately beholden to old forms of knowledge to defeat the monster. In a time when we can pull out our phones and Google any question that pops into our heads, I think there is a lot of appeal in the idea that there are some things that remain shadowy and unknowable.

A.D. Amorosi: How would you say that Stoker’s “Dracula” speaks to ways that relate to the Mütter Museum – its curators, its audience – enough so to build, and gear a “year” around him, and a series of exhibitions?

Meredith Sellers: There are so many connections between horror and medicine, especially when you’re looking at the nineteenth century. It was a time of unparalleled advancements in scientific understanding and technology, but also a time where old ideas, superstitions and folklore still had a strong hold on society. While medicine came to understand the causes of many diseases in that time period, it still had relatively few cures, leaving gaps for more sinister solutions to take hold in times of desperation. There is an incredible wealth of material and topics related to Dracula, and the vampire is such an enduring pop-cultural icon that it seemed obvious we needed to do more. So, we’ve expanded beyond our small case exhibit and are using multiple events and programming to explore various ideas including the novel’s use of physiognomy, the discredited 19th century pseudo-science of reading faces, which my colleague Kevin Impellizeri will talk about in a virtual happy hour on October 12th; the intersection of medicine and the occult, as exemplified by the character Abraham Van Helsing, which we’ll discuss in our screening of Häxan on October 16th; pop-ups on diseases that may have informed the vampire myth, a blood drive on January 7th, and additional screenings of two vampire films, Thirst and Interview with the Vampire in February and May, respectively.

A.D. Amorosi: What can you say about this case, the coffin-shaped exhibit where people in the Victorian era would be able to identify a body as a vampire? What it looks like and what it says about Dracula’s legend?

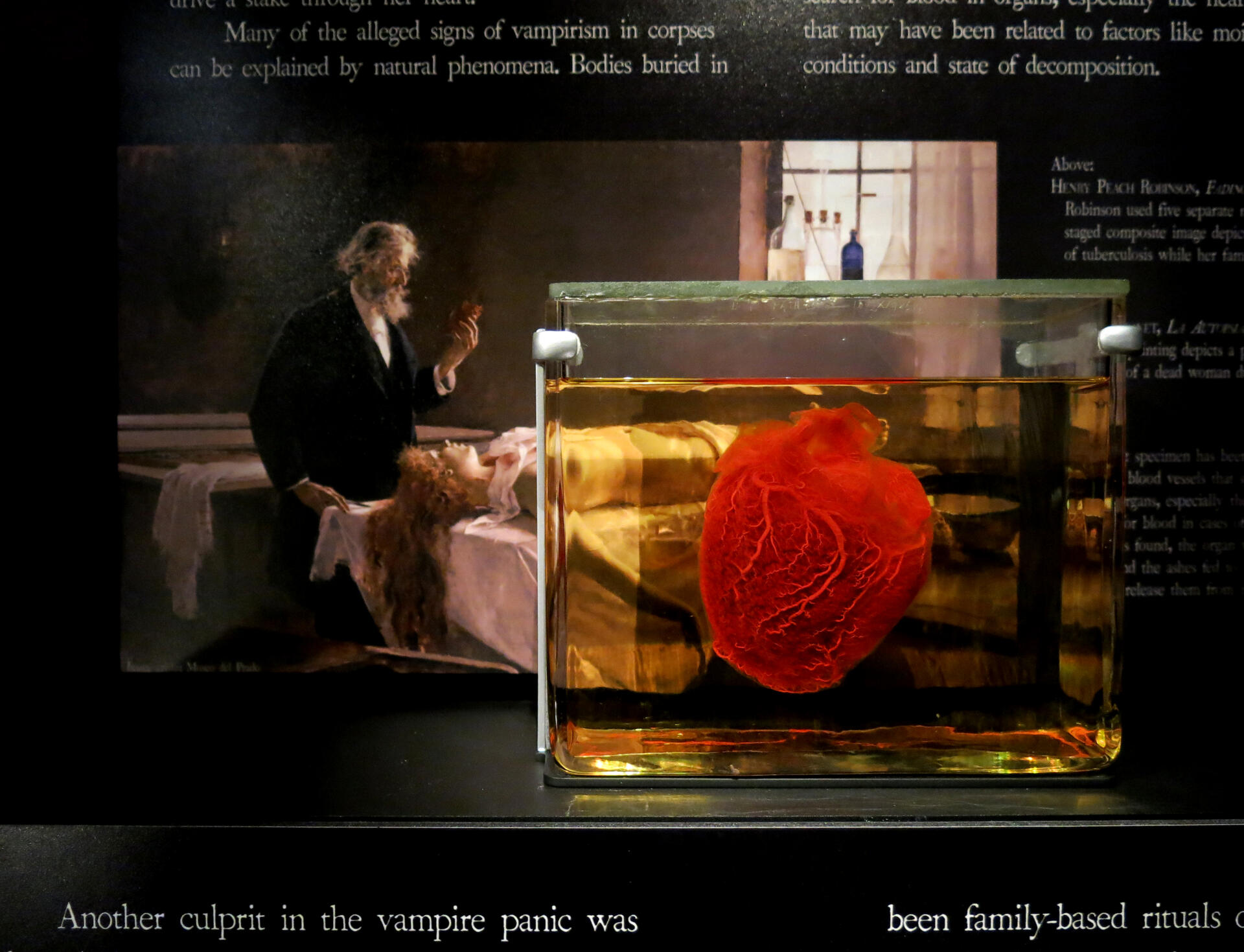

Meredith Sellers: Our case exhibit features a large glass front, which has been blacked out the create the shape of a coffin. Inside, an autopsy kit is open, its rib shears, skull chisel, and dissecting scalpel and hook splayed out. A vermillion heart glows at chest level, and a Vampire Killing Kit, on loan from the Mercer Museum is displayed at the foot of the case. The exhibit examines what people were looking for when they exhumed corpses in search of a vampire. An obvious one is an uncanny state of preservation, but they would also often do a crude autopsy, open up the chest cavity, and look for blood in the heart or other organs. Most of the assumed signs of vampirism can be explained by factors of natural decomposition or weather.

A.D. Amorosi: How real is the Vampire Killing Kit? It looks intense.

Meredith Sellers: The Vampire Killing Kit, it should be noted, is fascinating but likely not an actual antique. Rather, due to some compounds found in the paper, adhesives, and other objects, we believe it contains some antique items, such as the gun, the ivory crucifix, glass vials, and bullet mold, but it was probably assembled at some time in the second half of the twentieth century and passed off as authentic. The exhibit, however, really deals with the power of belief, so it seemed appropriate to include the Vampire Killing Kit as a testament to the continued pop-cultural fascination with vampires.

A.D. Amorosi: Such mournful but fascinating diseases like tuberculosis, led to post-mortem identifications of ordinary citizens as vampires in the 19th Century. I know that panic accompanied this. Can you tell me a little bit about what this phenomenon held, and how It is portrayed in the exhibition?

Meredith Sellers: Vampire panics, in the US and elsewhere, were often preceded by cases of tuberculosis circulating in the community. Pulmonary tuberculosis, the kind that resides in the lungs, presents as a kind of wasting away, where the sick person becomes very pale, weak, and coughs up blood. It happens slowly, usually over a period of several years. The symptoms of tuberculosis essentially mirror the languid wasting away that the supposed victim of a vampire experiences as the monster feeds upon them. By the time Dracula was published in 1897, fifteen years had passed since Robert Koch definitively proved that tuberculosis was caused by a bacterial infection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, however, there wasn’t an effective cure for the disease until the 1950s. So, although nineteenth century doctors could correctly diagnose someone with tuberculosis, they weren’t able to offer any cure. If your neighbors, your friends, and your family are all dying and your doctor tell you he has no cure, you might not have much use for his diagnosis. To understand the vampire panic, you have to understand the desperation people must have felt in order to desecrate the grave of a loved one in the hopes of saving another. Where science falls short, other explanations and solutions will arise to fill the vacuum. In lieu of a physical object representing tuberculosis, in the exhibit we’ve used an 1858 image by Henry Peach Robinson called Fading Away. It shows a young girl dying of tuberculosis, surrounded by her grieving family. The image itself is a staged composite photograph but it is such a powerful depiction of the romantic “beautiful death” that tuberculosis represented to Victorians, and it also shows how the disease impacted families.

A.D. Amorosi: HBO Max’s Irma Vep, the AMC Network’s re-do of Interview with a Vampire, Renfield starring Nicolas Cage as Dracula, the upcoming production of Nosferatu: the vampire as a cultural touchstone never dies – why?

Meredith Sellers: The Vampire has a shape-shifting quality—it has been a metaphor for disease, for sexuality, for the Other—its ambiguity makes it a potent symbol that continues to embody our fears and our fantasies. And, of course, the vampire itself is immortal, so, naturally, it never dies.