Banned Books Week has several days left to go, and still, when confronted with the list of classics – old, new – that have been ripped from shelves, schools, salons and stores, the mind absolutely reels. What level of prurient mind would make it that the likes of Joseph Heller’s satirical Catch 22, Ray Bradbury’s dystopian Fahrenheit 451, Ernest Hemingway’s dramatic For Whom the Bell Tolls, Judy Blume’s weary Are You There God? It’s Me and Anonymous’ harrowing Go Ask Alice would be shaved from bookshops and libraries?

David Levithan knows.

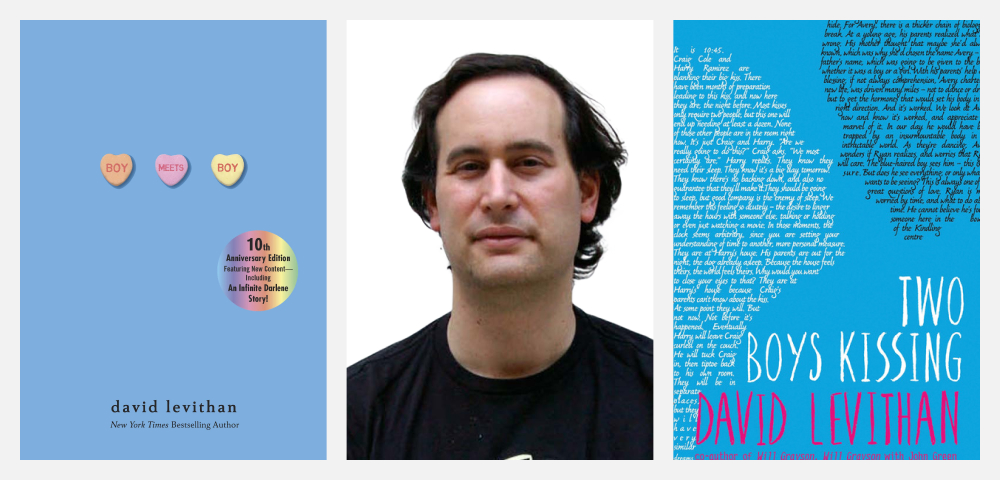

As a one-time editor and publisher at Scholastic Books, Levithan oversaw author Alex Gino’s George, a book challenged for its take on a transgender youth. As a beloved writer of YA queer literature, Levithan’s ban-a-bility has been put to the test with works such as his 2003 debut, Boy Meets Boy, and the popular 2013 release, Two Boys Kissing.

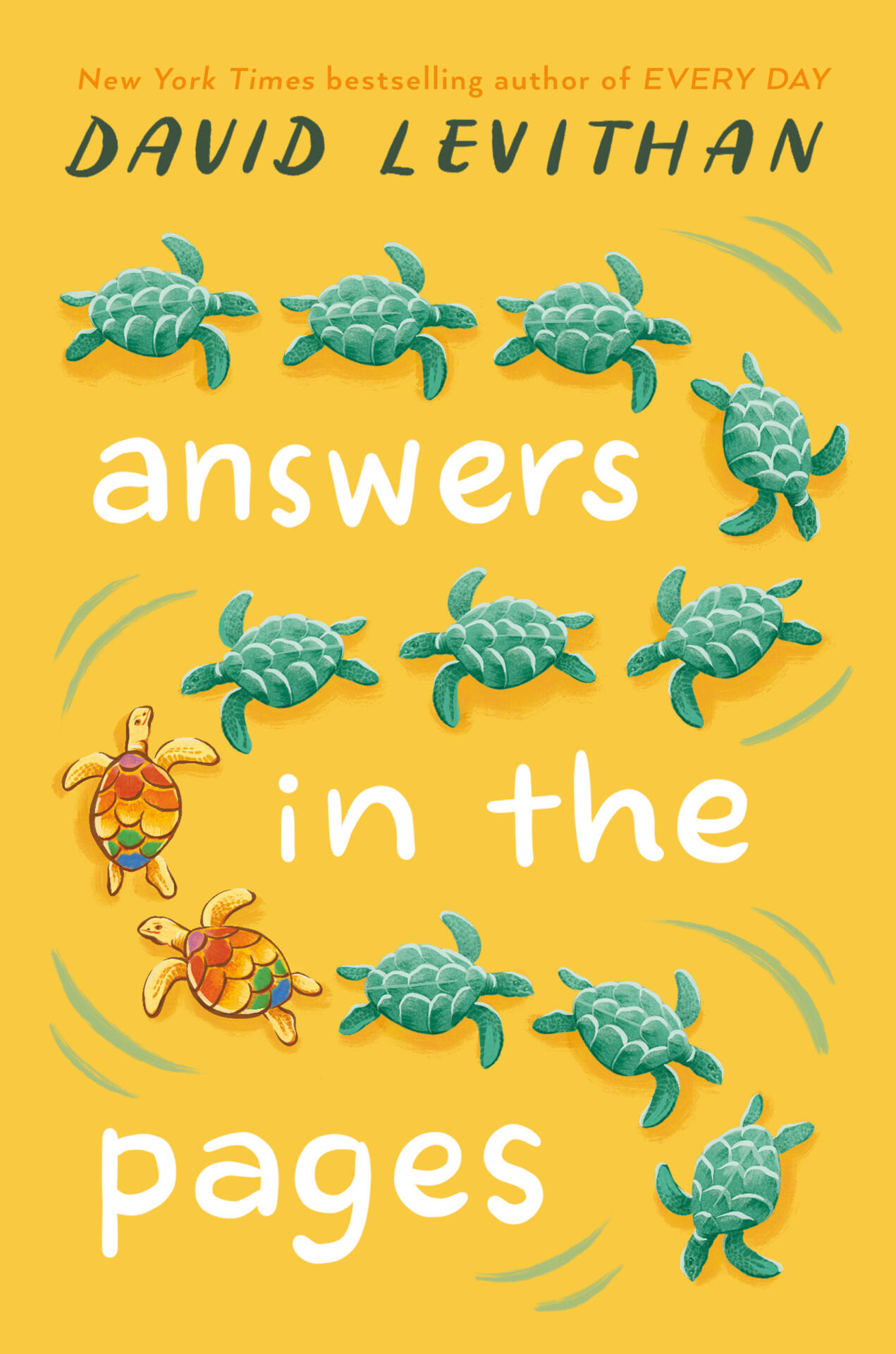

“When I wrote this book in late 2020 and early 2021, I had no idea it would come out at a time when politicians were trying to use books ꟷespecially books by queer and BIPOC authors ꟷas political tools, trying to dress up censorship in ‘pro-family, pro-parent’ clothing that is lined with age-old homophobia and racism.”

Levithan is talking about Answers in the Pages, his newest volume that tackles books banned and challenged, most of which reflect diversity and warm to inclusivity.

Philadelphia Weekly’s A.D. Amorosi spoke with Levithan about all sides of the censorship of the written word in a mid-week interview.

A.D. Amorosi: Before I discuss you, I’m curious to get your opinion of The Top 10 Challenged Books of 2021 detailed here: https://bannedbooksweek.org/about/?

David Levithan: I can’t say I’m particularly shocked. BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ authors are being targeted, and this list certainly reflects that.

A.D. Amorosi: Answers in the Pages more often than not is apt to take on books that are challenged or banned or considered troubling due to their level of inclusivity and diversity. Beyond this phenomenon, what do you recall of the first “banned books” you ever witnessed – I can recall everything from William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch to Nabokov’s Lolita – and what was your impression of a government, local/scholastic or national taking on the responsibility of what its people should and shouldn’t read?

David Levithan: I was lucky because no constraints were ever put on my reading. I’m sure I became aware of banned books because of my school library doing a display, highlighting the titles that were being banned in other places. I remember Catcher in the Rye being on the display . . . and when I read it I was expecting something shocking. But I finished and couldn’t comprehend why it had been banned.

A.D. Amorosi: You edited Alex Gino’s George which was certainly an often challenged book. What was it like from the immediate outside? And how did that incident prepare (or not prepare) you for Boy Meets Boy and Two Boys Kissing being challenged?

David Levithan: I was proud to have my own book on the same list as a book I had edited. (This has happened a few times.) I think all of us who’ve been through challenges have a lot of counsel to give one another, especially when the challenge is really about your identity, not the language you’ve used. All of us are exhausted by having to deal with bigots, and all of us are energized by the students and educators who come to our books’ defense. When it’s your book under attack, it’s helpful to talk to someone who’s gone or is going through the same thing.

A.D. Amorosi: Emotionally what does it feel like to have one’s works challenged and banned? Aesthetically what does it feel like?

David Levithan: On the one hand, you’re proud that something you’ve written is speaking for voices that the censors are trying to silence. On the other hand, you’re concerned that a whole lot of people (librarians, booksellers, students, parents, teachers) are on the front lines defending your book, in some cases putting their jobs or their relationships with other members of their community at risk. In terms of aesthetics . . . that doesn’t really come into it. I know the people attacking my book either haven’t read it or have grossly misread it. Their opinion of my work doesn’t mean anything to me.

A.D. Amorosi: Focusing on the challenges to books in schools, especially when it comes to BiPoc and/or queer themed books and authors – what is the first thing that you are hearing from those doing the banning: the principals, the libraires, the teachers, the keepers of the school district?

David Levithan: Playground taunts and misinformation.

A.D. Amorosi: What are you noticing about the commonalities that exist with those doing the banning?

David Levithan: It’s an organized effort, aiming to use book censorship as a means to overthrow public education in this country. While it’s based in racism and homophobia, it’s also based in the desire for profit and the complete disregard for disadvantaged or marginalized students. What we’re seeing now isn’t one parent complaining on their own about a book their child is reading, based on them reading the book. No, the people protesting and legislating and demanding are doing it for political reasons. It’s unlike anything we’ve ever seen before, and it’s scary as hell.

A.D. Amorosi: What was the last straw, the one that made you write Answers in the Pages?

David Levithan: I wrote Answers in the Pages to honor all the kids and educators who defend the freedom to read. It’s an optimistic book, because despite being scared as hell, I have seen time and again that people do NOT want other people telling them what they can or can’t read, and they will stand up for this principle.

A.D. Amorosi: In its writing and research, what was the toughest ban or concept on banning that fills Answers in the Pages?

David Levithan: I deliberately kept the book focused on the local, because I felt when I was writing it that the local level was where these battles needed to be fought and won. If I were writing the book now, I would have to include the influence of the national level, and the way these outside groups come in and try to tell a community what they can or can’t read.

A.D. Amorosi: By book’s end, what level of hope or call to activism should readers derive from Answers in the Pages?

David Levithan: The hopeful part is that kids understand the right to read. I have never heard of a book challenge being lodged by a kid or a teen. It’s always the adults who are trying to take away the right, and the kids who will fight for it. The kids give me hope.

A.D. Amorosi: What does Banned Books Week say to you about the continued issue of censorship and totalitarianism?

David Levithan: Now more than ever, we need to be vigilant, and we need to vote in elections at every level, and we need to make sure that all kids see themselves on the shelves. If you care about the right to read, vote in your school board elections, and make sure the people you vote for care about the right to read as well.