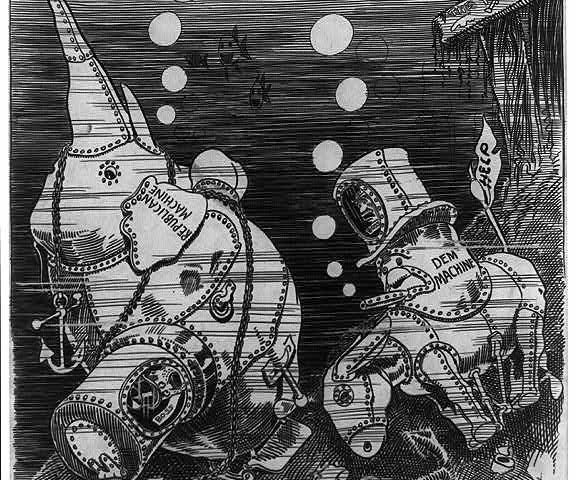

This city has always had a corruption problem. For one moment in the early 1950s, though, we rose above it and passed a new charter infused with a reforming spirit of good government. Ever since, machine politicians have been trying to tear it down and go back to the bad old days of “corrupt and contented” Philadelphia.

With passage of this election’s Question 3, the latest proposed change to the City Charter, they may finally succeed. Presented as an “equity” measure, it has nothing to do with race and everything to do with power.

Before the 1951 Charter, city employment was a pure patronage system. Anyone applying for any position would get the job through political connections in the then-dominant Republican Party machine. Ward leaders controlled the jobs and merit and talent had nothing to do with it. This inevitably led to corruption. When city employees did their jobs poorly, nothing was done about it: all of the offenders were politically connected and untouchable.

Eventually, even complacent Philadelphians began to demand change. In 1947, a committee of civic leaders was formed to investigate. After decades, the whole rotten thing began to unravel. Their report the following year showed widespread embezzlement and hundreds of workers who collected a paycheck without performing any actual labor, or even showing up. Grand juries were convened and corruption exposed.

The scandal was enough to make Philadelphians abandon a loyalty to the Republican Party that stretched back to the Civil War. They approved a new, reform-minded City Charter in April 1951 and elected a ticket supported by Democrats and independents later that year. For the first time, Philadelphia looked at itself and thought “we can do better.” Mayor Joseph S. Clark and District Attorney Richardson Dilworth led the charge.

For a brief time, they actually cleaned up this city. Part of that change came in the City Charter, which enshrined the principle of merit selection. Instead of hiring based on political connections, the city would be required to offer a civil service exam. According to section 7-401 of the new charter, positions would be filled by choosing between “the two persons standing highest on the appropriate eligible list to fill a vacancy.” No more cronyism, only the best person for the job.

The reform spirit began to wane almost immediately. By 1955, as reformers on City Council began to be replaced by party machine men, there arose a majority in favor of repealing merit selection after just four years. The voters defeated these amendments in a 1956 referendum, but the reform movement was effectively at an end.

It is that same section 7-401 that City Council wants us to change on Tuesday. And by “change” they mean “effectively eliminate.” Instead of the top two qualifiers, those in charge of hiring would now be able to choose from “such number of persons as determined by the Personnel Director” based on the needs of the department. This turns a concrete requirement into no requirement at all. If the political bosses want a certain person hired, all they need to do is tell the Personnel Director to change the numbers. It is a fraud.

Why, after all these years, would Philadelphians want to abandon the city’s commitment to honest hiring practices? Because this wolf of a resolution is dressed up in the sheep’s clothing of wokeness.

According to the law’s sponsor, City Council Majority Leader Cherelle Parker, the change would give those in charge of hiring “more flexibility to address recruitment and diversity challenges.” That is to say, she wants the city to take race into account when hiring and the city charter stands in the way of that. The tests are biased, they say, but instead of fixing the tests they will just make them irrelevant.

It is ironic, given that the civil service reform of the 1950s was praised by leaders of Philadelphia’s black community as a way to take hiring decisions out of the hands of well-connected white ward leaders. This is the lesson of the Enlightenment: when the principles of meritocracy are applied without discrimination, everyone has a fair chance at success. The drive for honest government was, at heart, a drive for fairness and the American Dream.

People in power never like any restrictions on themselves. The city’s political bosses’ attempt to weaken merit selection is no surprise. What is surprising, and dismaying, is the acquiescence of people who once took a prominent role in cleaning up Philadelphia’s corruption.

David Thornburgh of the nonpartisan Committee of Seventy praised the effort to destroy reforms for which his organization once labored. “Reform of the 1950s-era Rule of Two has long been needed to provide greater flexibility in hiring and promotion decisions,” Parker’s website quotes him as saying. “The rigidity of the Rule of Two was warranted 70 years ago to guard against patronage, but we face a different set of challenges in the 21st Century.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, too, endorses the change, a reversal of their longstanding editorial commitment to civil service reform.

Afraid of being tarred as racists, civic leaders have given up on the reforms that marked the brightest period in Philadelphia history. The “best person for the job” will no longer apply to the city’s hiring practices. Cronyism will reign unchallenged. Clark and Dilworth are dead; if Question 3 passes, civil service reform will be buried with them.