After all these years, do we really know Bob Clarke?

The scenario borders on unbelievable, if only because Philadelphians think they know the man involved, inside and out. He’s long been part of the city’s competitive fabric, so most people already have an opinion.

Love. Hate. Not much in between.

But ask his son-in-law, also a hockey player, whether the outsiders really know the man and he laughs. He thinks and small-talks for a minute before sharing a scene that answers the question for him.

“What people usually see is him at a press conference,” says Peter White, standing near the Zamboni entrance at a South Jersey hockey rink. His sweat-soaked practice gear is already stashed in the locker room he shares with his minor-league teammates down the hall from the big leaguers. “They don’t see him when he’s down on the living-room floor, one of his grandkids on his back, playing horsy, trying to buck them off of him.”

Hold on. A doting grandpop playing horsy? Nope. Can’t be. The guy’s known for grit and has a penchant for dishing out nasty cheap shots from time to time, right? Hell, he’s even been called one of the dirtiest players ever.

Leading a rough-and-tumble team, he never got booed by the fickle hometown fans. He captained that brutish squad about which an opponent once recalled, “Everybody would be happy-go-lucky on the bus ride down to Philly, but as soon as you hit the [Walt Whitman] bridge and saw the Spectrum, all the smiles were wiped off our faces, … your stomach started to quease a little bit.”

No, an intimidator doesn’t play living-room rodeo with an ear-to-ear smile on his face. Or does he?

“There’s a lot more to him,” White explains, “than what people think.”

The “him,” of course, is Bob Clarke, a man who really doesn’t need much of a formal introduction around these parts.

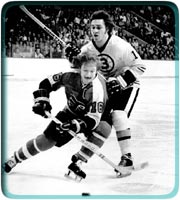

Captain and heart and soul of a two-time Stanley Cup championship team. Three-time league MVP. Nine-time All-Star. Peerless leader who went straight from the ice to the front office when he retired in 1984. The face of a franchise with a burning will to win that consumed his life, Clarke’s number 16 is just one of four hanging from the rafters down in South Philly. (All four played on those Broad Street Bullies teams.)

And the “people” White talks about are Philadelphia Flyers fans who can’t reconcile whether their living legend does well by always keeping their beloved team in contention or if he’s just living off the blind loyalty of a boss who refuses to punish him, even though he hasn’t delivered a championship in nearly three decades.

Both camps can make lucid arguments, and thanks to sports talk radio, they do just that — usually when there’s nothing Eagles, Phillies or Sixers worth discussing.

But what do we really know about the man?

Sure, there’s the oft-told tale of a skinny kid with diabetes beating a bunch of odds to become a hero. And countless stories from his latter years as a general manager who’s harbored grudges while never matching his on-ice victories since crossing that management line. On Comcast’s website, he’s “the ultimate Flyer” who’s married to wife Sandy, has four children (sons Wade and Lucas and daughters Jody and Jakki) and resides in Moorestown, N.J.

Unforgettable, city-altering successes? He’s got ’em. Two million people flooded the streets to celebrate his team’s first championship in May 1974 and the second, which came a year later. And that’s without mentioning how his red hatred helped push the team past a seemingly infallible Soviet Red Army team two years later.

Startling, almost inexplicable controversies? They’ve started to fill the latter half in the book on his life. Not to mention countless pages of newsprint in recent years. (Um, need we even invoke that certain former player’s name? Well, the closest he came to doing so is saying he’s always despised the New York Rangers, and continues to hate some of the players on the current team.)

There’s more of course, but the whole story hasn’t been told.

Blame that, in part, on the fact that the man doesn’t really seem to like talking about himself. He fields questions with a smile (or scowl, depending upon the topic), gives the quick answer and next thing you know, he’s already on to something else. And who, really, is going to put words in Bob Clarke’s mouth?

Perhaps it has to do with a city that probably doesn’t really want to humanize someone who’s performed superhuman feats on their behalf. And replaced their defeatism with civic pride along the way.

As a result, the question becomes this: Is it fair to pass personal judgment about a man that this city may never have really known as well as it thought?

Saying yes deprives him of a fair shake, even though he’ll tell you he’s not really looking for one. Doing his best at work is good enough for his conscience.

Saying no ushers in a whole new set of challenges, like actually figuring out how to get him to talk publicly about things non-hockey. (Turns out just asking gets him to open up — a little bit, at least.) But if the story’s going to be told, it had better happen soon.

Having assembled a team that’s not getting much younger and doesn’t have the premiere goalie coveted by fans, the prospects of hoisting the Stanley Cup grows dimmer each year. In a championship-starved city such as this one, each failed campaign intensifies the calls for his head on a platter.

Then throw in the fact that the National Hockey League is careening toward a potentially devastating work stoppage that could doom it to second-tier status once and for all. (By this time next year, the league’s collective bargaining agreement with the player’s association will expire. Since it’s a financially struggling league, should a salary cap not be invoked, a lockout is likely.)

So today, just one week before the 2003-04 orange-and-black embarks on what may quickly become a do-or-die season for the players, their general manager and their sport as a whole, it’s time to find out just who Clarke really is — while the answer is still relevant.

Training camp is just three days old but there’s a sense of excitement around the Flyers Skate Zone in Voorhees, N.J.

The fans, many sporting the jerseys of their favorite players, arrive en masse — probably about a 100 a day, there to watch their squad prepare for another season or catch them for a quick autograph before they zoom past in their SUVs and sports cars.

Inside, the faithful line the bleachers along the side of the ice. They snap pictures. They ooh. They aah. The kids try to get their hands on broken sticks and extra pucks. Others wave through the glass at their heroes. True believers whisper that maybe this is the year. Some hockey-minded folks, after all, say they are contenders.

Here, Clarke gets the Mister treatment before his name. There’s a reverence when the fans talk about him.

“He was the best. Everybody’s hero. I still think he’s a good GM. [His moves] might not always pan out, but he tries. Maybe one of these days, it’ll all work out,” says Mike Murphy, a water company worker from Atco.

“He is Philly hockey,” says Mike Pisco of Glenside. “He’s the right person for the organization, even though he could’ve made some better decisions. There’s a lot of discord surrounding him. Maybe he’ll figure it all out for himself this year.”

About 15 feet above them all, a balcony juts out from the second-floor offices, overlooking the rink.

It has the feel of an emperor’s box at the Coliseum in Rome, but instead of deciding who lives and who dies, those gathered over the masses are evaluating who makes the pro roster and who gets relegated to the Phantoms minor-league squad.

To the tight little subculture of hardcore Flyers fandom, the faces up there are familiar. There’s Dorney and Coatsey, the broadcasters. Taking a break from his on-ice duties, Coach Ken Hitchcock is up there as well. Hey, isn’t that Hexy? (Or Ron Hextall, the mainstay goalie who carried them to a Cup finals in his rookie season, but now has a front-office gig as personnel director.) And finally, there’s square-jawed Paul Holmgren, another former player and coach who made the leap to management as assistant GM.

Of course, the one who turns the most heads — not to mention drawing a few cameras in his direction — is the man on the end.

His face is unmistakable, even though he’s gotten all those missing teeth replaced. He’s wearing khaki shorts and a baseball hat, brim forward. His black Phantoms windbreaker, collar up, is the only concession he makes to the cold rink air.

As Clarke’s eyes follow each play; he doesn’t seem to say that much. With the players still scrimmaging, Clarke can’t yet leave his perch. “Player evaluations,” explains Flyers PR man Zack Hill. “He can’t talk until after this period.”

The play continues. He keeps watching, which is what he’s supposed to be doing since the success of a franchise is entrusted to his decision-making ability. Every player who makes the team is there at his behest.

With 30 seconds remaining, he disappears in a flash. Without watching his every move, it’d be easy to miss him duck back into an office that has a wall of windows opening out onto the rink.

The desk? No computer, but there’s a puck and a stack of papers. The walls? Hanging there are, among other things, a scorecard from an epic five-overtime battle of a few playoff runs past and a plaque commemorating another player’s Flyers Hall of Fame induction ceremony. Why are there no personal mementos? “I can’t understand why people would want to make their office a museum to themselves,” he says, noting that hockey could be the most important thing in his life.

If he really hates the media, as some contend, he doesn’t let it show when he’s introduced to the reporter and photographer whom he knows are there to dig into his life, if but for a few hours. He smiles, shakes hands and sits behind that large desk, assuming his guests know they can just sit down on the couch or at the table.

It only takes a few minutes for Clarke to say he can’t remember the first time that he was booed. And that even if he could, he doesn’t let things he can’t control bother him.

No, he’s not interested in analyzing what other people say, or think, about him. How can he read other people’s minds? Why should he bother? It’s not like he’s going to change anybody’s mind now. Especially those of people like one Canadian broadcaster who recently said he acted like “some freaked-out paranoid schizophrenic.”

He concedes that mistakes have been made. By him. But that it’s just part of the job. He’s not the first GM to make bad personnel calls and he most certainly won’t be the last, goes his thinking.

And then, the topic turns to who he is.

Not Bobby Clarke, player.

Nor Bob Clarke, general manager.

Bob Clarke, 54, father of four. Son of a miner, born in Flin Flon, Manitoba.

“There’s really not that much to know,” he says, almost smirking. “I’m pretty uncomplicated.”

Uncomplicated, eh? No, most will tell you, Clarke is anything but uncomplicated. The critics say they can’t figure out what’s going on in his head. (The fact that it’s hard to goad him into a discussion about those controversies doesn’t help them all that much.) The fans have no background that would tell them what he’s all about, personally, either.

But to him, it all makes perfect sense.

“The whole thing never changes for me. Every year, it’s about trying to win the Cup,” he explains. “I’ve set out to give my best, which is what I’ve done my whole life. Some people may question that but I set out to do the best I can. … If you want to be successful at this level, you’d better be strong because wimps just can’t cut it.”

For good reason, if only self-preservation, few people call him a wimp. Even without the hockey, his daily regimen screams that he’s a man’s man.

Take the Cherry Hill gym he runs, for instance. Clarke, who has his grandchildren’s names tattooed on his wrist, refers to it as a “men’s gym,” as he should, since there ain’t a woman to be seen in the place.

His former teammate and good friend, Bobby “The Chief” Taylor, says Clarke snatched the place up to prevent a chain from taking it coed. These days, Clarke gets there by 6 a.m., gets his workout in and then hangs out with his friends, many of whom are local police officers and state troopers, according to Taylor. (“He probably loses his shirt on the place, but that’s the kind of guy he is, buying it so the guys could keep it the way they had it,” Taylor says.)

“They’re sports fans, yeah, but they’re friends from outside of hockey,” is what Clarke says of the men with whom he grabs breakfast at Ponzio’s, a nearby diner, in the mornings. “Eggs. Nothing special. Eggs,” he says.

From there, it’s off to the rink where, in the past year, he figures he’s skated about a half-dozen times.

“Just going out there and fooling around a bit. I’m too lazy to put all that equipment on, especially after working out,” he laughs. Asked how he’d fare against today’s pros, Clarke mulls the question for a moment before declaring, “I’d be a decent player. I’d figure it out. Sure, they’re bigger, faster and stronger, but guys who play the game, play the game.”

He doesn’t listen to 610-WIP, by the way, choosing instead to listen to oldies when he drives. The papers? Sure he reads them, but doesn’t pay the sports section all that much mind. He will say, however, that he respects guys like Phillies slugger Jim Thome and Eagles quarterback Donovan McNabb, since they know they’re talented but don’t resort to rubbing it in their opponents’ faces. He also respects Phillies manager Larry Bowa for “wearing his heart on his sleeve.”

“I enjoy reading, but I’m more interested in what’s going on in the world. I already know about sports, so why read about it?” Clarke offers. “I’m really paying attention to the [Philadelphia] mayor’s race now.”

Some nights, he can be found at P.J. Whelihan’s in Westmont, N.J., not all that far from Rexy’s, the restaurant where he and his old teammates used to hold court in the ’70s. For the most part, he’s left alone to enjoy his bar time. His perch is entirely across the room from where a lithograph depicting him and Eric Lindros together hung before a recent renovation.

Ask him what his favorite beer is and he jokingly asks, “Are there any bad ones?” before conceding Miller Lite and Coors Light are often his beverages of choice. “I really like draught beer, though. That way they can’t count how many you’ve had.”

And yes, even though he was born and raised in Canada, and still visits his hometown like he did for a week this past summer, he’s proud to be a Philadelphian. The only time fame really interfered with his ability to live a good life was way back in those championship years, when he had to move.

“When the bars closed at night, we’d have people knocking on the doors,” he says. “And then, you’d have some who’d walk right into the backyard when we were out there.”

Having been here for more than three decades now, he says he “wouldn’t want to call anywhere else home. … It’s hard for me to imagine that any place could have been as good to me as this one has.”

Ask people who know him well about what kind of guy he is, and the answer differs from Clarke’s guarded one.

“I don’t think there’s a dog on Earth that’s more loyal than Bob Clarke,” says Taylor, recounting how his friend would give gifts away to team trainers rather than keep them for himself. Clarke is also the godfather of Taylor’s son, Casey. “OK, maybe he’s not outwardly affectionate, but you can tell he cares about his friends. If you’re his friend, you’re his friend for life.

“I’m obviously biased when it comes to him, but he’s just an amazing guy. He’d go to the end of the world for you.”

Yeah, but is he funny? Well, The Chief thinks so.

“Oh, he has an unbelievable wit. Biting. Sharp. You know how guys like to bust balls,” he says. “Well, we were having a party for Barry Ashbee [a Flyers legend who died of leukemia in 1977] and somebody bought him a pair of binoculars, since he was an outdoors guy. Well, Ashbee’s lost his eye, what a dumb gift, right? So what does Clarke say? “Shoulda got him a telescope.’”

Then there’s Comcast-Spectacor Chairman (read: Flyers owner) Ed Snider, who’s stood behind his franchise star through the tumultuous years. He recalls instances of Clarke getting endorsement deals, only to split his profits with teammates.

Says Hitchcock, the current coach, “You feel his focus. You know what’s up. Clarke’s a guy that, if you show him loyalty, he’s there for you no matter what. … To say what you feel, to feel what you say, that’s a great quality.”

Even Wayne Cashman, the former Flyers coach — one of many fired by Clarke — who played on the Boston team that they defeated to win the 1974 Stanley Cup, has some kind things to say.

“He just does things and doesn’t tell anybody about it. Maybe he doesn’t think it’s a big deal, but for the people he helps, it really is,” he says. Cashman needn’t tell that to Dave Poulin, the former Flyers captain who got the “C” on his jersey in his second season, courtesy of Clarke’s decision to hang up his skates. Poulin says Clarke’s generosity helped shape a successful career. Today, as coach at the University of Notre Dame, Poulin recalls coming to Philadelphia at the end of the 1982 season. He didn’t have a car. He didn’t have a place to stay. So when Clarke found out about these things, he had Poulin meet him at a car dealership — “You can turn it over to him. I’ll sign for it,” he recalls Clarke telling the salesman — and told him to sublet a place near his own.

From there, it was on to a summer of working out together, the legend imparting wisdom with an up-and-comer. To this day, Clarke says his biggest mistake as a GM was trading Poulin to Boston in 1990. (For his part, Poulin says it was probably for the best as it resurrected his career. Still, he’s taken aback when told that Clarke considers the trade among the worst moves he’s ever made.)

“Here I am having only played five games, and I’m spending the summer training with a legend?” Poulin says. “There’s no question he changed my life.”

Despite those close ties, Poulin sees Clarke as more than a sporting icon, something that helps explain Snider’s apparent unconditional loyalty.

“He was as important to building a franchise as anybody has ever been in sports,” says Poulin, who graduated Notre Dame with a business degree. “He was the central figure in what became a very successful business and all the ancillary things that came out of it, a TV station, a management group, a security company. All those seeds were planted by Bob Clarke, the player and the person.”

What must be noted, however, is that most people who talked about Clarke mentioned that he’d probably be mad at them for talking. They laughed, but didn’t seem to be joking.

For Clarke, it always seems to come down to results, even though he hasn’t managed a team to the Cup. For the past eight or nine years, they’ve put a respectable team on the ice. They’ve made playoff runs, going as far as the finals three times since 1984.

He understands the close-isn’t-good-enough mentality that has fans devouring the Eagles alive this year, but doesn’t entirely accept it. As an aside, he chastises the people who’ve been booing the football team. He considers people who’d throw a bottle at the quarterback nothing short of degenerates and questions why on Earth the press would be taking personal shots at the team’s coach.

When the conversation returns to hockey, he says of course he’s disappointed with a team that’s fallen short when the playoffs roll around each year, but at least they have a shot, which is more than a lot of teams can say. “Last year, we were close, but we have to improve on that. This organization is dedicated to having a good team and to be a good team, we have to do better in the playoffs,” he says.

In fact, those expectations left Clarke boiling over at the end of the 2001-02 season when the Daily News ran a back-page headline that screamed, “Fire Mr. Flyer.” Letting the story stick in his craw another four months, he lashed out in an interview with another writer for the paper as last season’s camp opened.

“I don’t have anything to prove to you people. I’ve won in this league. … If the writers judged themselves the way they judge me, they would all be fired,” he was quoted as saying. “The papers are losing readers, they’re losing advertisers, losing money, everything. But you never judge yourselves. You judge me. You say that I should be fired. Maybe it should be you guys that are fired.”

He’s had some ample opportunity to cool off but sticks to his guns today. The press, according to Clarke, still needs to learn the skill of being critical without personally criticizing.

“The media has changed a lot since I first came here, but so has everybody else. I’ve changed too,” he now says. “There’s so much competition for a story that they want to get into personal lives, how much people are making. They can’t write about the games because fans can watch it on TV a hundred times before the paper comes out. If they want to sell papers, they have to find other stories.”

Does he dislike the press? Well, he knows they have a job to do.

“If you try to please them all the time, then you’re a public relations person, not a general manager. I’ve been given heck a lot of times, told that I have to be nicer to this particular media guy or that one,” he says. “But even if I don’t like them personally, I treat them the same as I treat everybody else.”

Having once confessed to letting hockey run his life, Clarke knows some think he’s a one-trick pony.

“My life is very narrow — well, at least that’s how it’s perceived by other people,” he says. “But, I’m happy here. I’m happy when I come to the rink. I’m happiest being around all this than anywhere else. It’s not like I don’t do anything else. I go to the gym. I play golf. I’m fairly content with where my life is right now.”

And with that comes yet another big question: Just where is his life right now? Professionally, at least, there’s a bit of turmoil. This summer, Snider took Clarke’s president title away. (Not a slight, they said, Ron Ryan had been doing those day-to-day franchise duties for years, so it was time for his title to reflect it.)

Then there’s the thought that having a strong, pedigreed coach like Hitchcock — he won the Cup with the Dallas Stars in 1999 — means the GM has less power with the team. And, to top it all off, the rumor mill has someone who Clarke hired this summer as a potential successor. (Dean Lombardi, the former GM of the San Jose franchise, fell into a major funk after being fired in March. Clarke, knowing the guy had to get up and dust himself off, offered that very opportunity, hiring him as a team scout.)

When asked about the future, Snider says he doesn’t think in “do-or-die” scenarios, even with the potential work stoppage looming.

He shares his thought that Clarke scores a B when it comes to his collective work since returning as Flyers GM in 1994. (Snider’s son, Jay, fired Clarke four years earlier, citing “fundamental differences” in deciding the team’s direction. After working for two other teams, Clarke came back, as Snider said “there was only one guy I wanted” for the job.)

“Bob is a competitor and a winner. He knows the game inside and out,” Snider said in a phone interview last week. “Two years ago, I was embarrassed [with an early playoff ouster] and Bob was embarrassed too. But last year, we were successful. We have an outstanding coach. We were one of the final eight teams and lost to the team with the best record. We’re taking steps in the right direction.”

Many gripes with Clarke go back further than the past season or two, though. Without even touching on Lindros — Clarke says the days of being constantly asked about it are in the past — critics say he’s traded people without getting enough in return. For a recent example, they point a deal this off-season that sent last year’s starting goaltender, Roman Cechmanek, to Los Angeles for a second-round draft pick. Making that sin worse is the fact that they say he’s brought it on by devaluing his players with his own mouth.

Others maintain that he stabbed longtime friend Bill Barber in the back by firing him as Flyers coach two seasons ago, when the team was apparently in mutiny. (Clarke says the two are fine today. A spokesperson for the Tampa Bay Lightning, where Barber caught on as director of player personnel, replied that it’s “not a topic he really wants to touch. I guess that’s the best way to put it.”)

And finally, they mention how, when former coach Roger Neilsen took ill, Clarke said it “wasn’t our fault, we didn’t tell him to go get cancer. It’s too bad that he did. We feel sorry for him, but then he went goofy on us.”

Defending his old pal, Taylor says people just don’t get Clarke.

“Obviously, he can be his own worst enemy when it comes to the press. He doesn’t think — or care — about what people think. He just does what he thinks is right,” Taylor says. “Everything’s so politically correct now it’s kind of like — whoa. Everybody gets knocked back when they get a guy who’s not worried about being PC. But you always know where you stand with him and you don’t have a lot of guys like that out there anymore.”

Adds Snider, “Bob gets pissed off when I say this, but he’s not great at public relations. A lot of things he’s said, when they’re taken out of context, or even if they’re in the right context, were not meant as they sounded.”

All those things helped spawn at least one anti-Clarke website — www.clarkemustgo.com — and has packed the message boards on another fan site, www.orangeandblack.net. One likens Clarke to “the GM version of herpes for the Flyers; there is no cure, we have him for life”; many others are supportive.

When he started the latter site six years ago, Cherry Hill resident Mike Barr stood by Clarke through thick and thin. Today, it’s a different story. Though Clarke’s his childhood hero, Barr thinks it’s time for the legend to move to another, less-important position in the franchise.

“People like me, who think he should be replaced, think that way for business reasons, not personal ones,” says Barr, noting that what really bothered him was that, before Hitchcock, Clarke continually hired and fired coaches, which destabilized the organization. “Sometimes he lacks couth. He says the wrong things, which makes the team and organization look bad. It’s time for a change.”

If anything, it seems that would be the ultimate insult to Clarke. He bleeds orange and black and says his world revolves around making the team better — even if others think he’s going about it all wrong.

So a couple Friday nights ago, there he was in the Wachovia Cente rafters. His chin firmly planted in his hands, he watched this year’s squad skate their way to a 6-1 preseason victory over the defending champion New Jersey Devils. (Sure, they played their starters against the opponent’s B-team, but it was the start of a campaign that has the Flyers doing anything they can to start filling the arena again. Their advertising push features Hitchcock, who’s been doing the bulk of media interviews so far, talking about a team that won’t back down. He urges fans to be a part of “the home-ice advantage”; it’s almost as if they’ve harkened back to a Broad Street Bullies vibe, a Bobby Clarke kind of hockey, because the future looks bleak.)

Down below was the rink, surrounded by the fans. Outside the guarded door to his box was the press. And when he ventured out into their lair between periods, he didn’t do interviews as he talked on his cell phone, acknowledging passersby with a smile. But when it came time to be really nice, it was for a young, jersey-sporting kid. “Hey pal!” Clarke said before he invited the child into the skybox.

With that, he was gone to prepare for yet another season. The fans are hoping a young defensive corps, meshed with veteran leadership, will make up for the lack of a show-stopping goalie.

As for the looming strike, Clarke said people better shake their greed. “These power-hungry people, they forget about all the people involved. The people who end up getting hurt are the ones who work at the arena, making a living for their family. We have a responsibility to everybody who makes a living off our sport,” he said.

When he was asked how he wants to see it all end, the conversation returned to past glories. He remembers hoisting the Cup at the Spectrum and cruising down Broad Street. Those things will never leave him and, in fact, they motivate him today. Clarke’s pretty sure a championship wouldn’t be as fulfilling as when he won two on the ice, but he’s eager to find out. From there? Well, he can’t really see himself doing anything else.

“I’ve heard that people think I should stop and smell the roses, maybe travel or something,” Clarke says. “Well, I’m not really a sightseer. I’m not ready to go to Vermont and watch the leaves change colors. The day that happens is the day they should just push me right off the Walt Whitman.”