The pandemic has been hard on SEPTA like it has been for many SEPTA riders. With revenue down, the transit authority needs to save money while maintaining or expanding service to those who rely upon it. It’s not an easy task.

But SEPTA management makes that task even harder when they throw money away on things that do not help riders get where they need to go. One example of waste: Spending $7 million on consultants and then refusing to implement their recommendations. At a time when SEPTA is plagued by a shortage of drivers, that money would be better spent on hiring and training new workers.

Ryan Briggs of WHYY’s PlanPhilly wrote earlier this month of SEPTA’s self-defeating consultant costs. With money bleeding out of the agency left and right in 2020, SEPTA’s management did what many corporate officers do in a crisis: ask someone else for answers. Briggs quotes Erik Johanson, SEPTA’s director of operating budgets, as saying, “We basically hired them to take us through the same sort of rigorous process that any Fortune 500 company, or all of our peers, had been going through.”

That is a big part of the problem.

Every company is different, and tax-supported transit agencies are especially different from private corporations. Yet, somehow, the standard choice in all of these boardrooms is to hire a bunch of people who have never worked in your industry to tell you how you’re doing it wrong.

Companies and bureaucracies (and things like SEPTA, a hybrid of the two) were once run by people who had worked in that industry for years. Boeing was run by engineers, GM by car guys, Pfizer by scientists. Who better to run an enterprise than people who had spent their careers in that line of work, possibly even at that very company? When some crisis emerged, the people in charge would know how to deal with it because they would have more experience in the job than nearly any outsider.

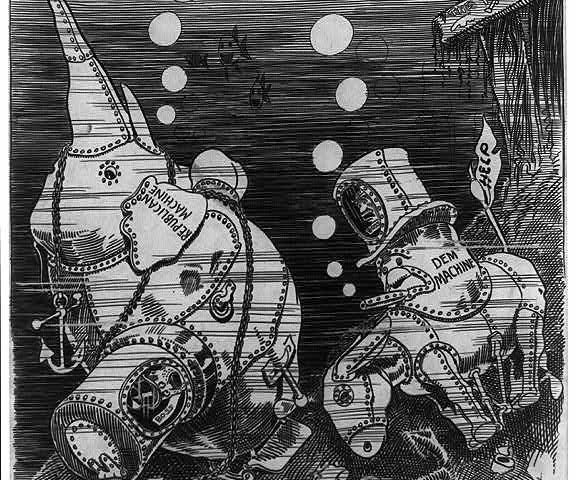

Today, CEOs are interchangeable finance guys, good at maximizing shareholder value without learning from the ground up how their product actually works. A public transit agency should be immune from such pressures, but instead SEPTA focuses on pleasing the political bosses who exercise power over it. It results in a group of executives who may be good at many things, but who are not experts in their own company’s business.

When things go south, they spend millions to find someone who is.

This is not the first time SEPTA has gone down this road. In 2012, they spent $2.8 million on a different set of consultants whom they hired in a no-bid contract. And for what? So that bright young people from Harvard and Yale can tell SEPTA what they’re doing wrong and SEPTA can ignore them? Why would anyone waste money in this fashion?

If they needed to figure out what to do in a crisis, the people hired to run the agency should know best how to do it. Need more advice from outsiders? SEPTA already has a Citizen Advisory Commission!

What does McKinsey give SEPTA that their own managers, workers, lawyers, and advisors can’t? The establishment stamp of approval.

The guy who drove a bus for 30 years might have some ideas on how to make the process better, but he doesn’t have what a thousand Pete Buttigieg clones in Manhattan do: a credential from an elite university. (Transportation Secretary and McKinsey alumnus Buttigieg himself did not consult on either of these boondoggles — though if he had, it would at least mean he would have gained some experience in the transportation industry).

When everything is run by financiers and politicians, it is natural for those in charge to look elsewhere for actual expertise. When the bright young things with the hefty price tags come along and look competent, it is easy to say “let them do it.” But what SEPTA’s experience shows — twice now! — is that no matter how impressively credentialled the consultants are, if they make suggestions that the workforce and management will never accept, it’s just throwing money down the drain.

SEPTA’s crisis of management is not unique, but they don’t have to go along with the rest of the government and business world in fixing it. Look within for expertise, promote people who understand the business, and let them find solutions that the union and management have a chance of actually accepting. Spend millions on riders, not consultants.