Ever since Howard Zinn popularized revisionist history in the 1970s, Columbus Day has become an annual fight between those who revere the past and those who want to revile it. As a holiday, it has been unusual from the start. Since the Great Awokening, though, Christopher Columbus and the celebrations he inspired have become radioactive on social media and even in parts of real life.

Columbus Day is unusual because it combines an ethnic group’s traditional celebration with the celebration of a great man and a larger lesson about American history and ideals. Most holidays involve just one of these, but Columbus Day has all three. Celebrations of the discovery of America were noted as early as 1792, the three hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s landing here. As the years passed and those celebrations grew more prominent, they became associated with America’s then-tiny Italian-American community as well as with American Catholics generally.

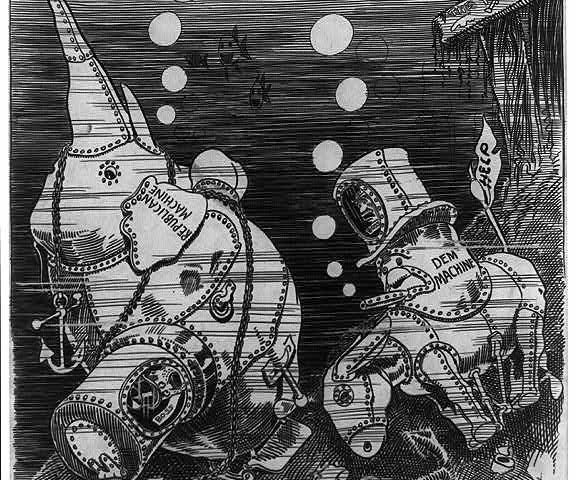

This was the first time Americans saw some opposition to the celebration. Long before the grievance studies gang came for Columbus, nativists tried to diminish his memory. The same anti-immigrant groups who burned Catholic churches in Philadelphia in 1854 also hated the public celebration of any Catholic, even one so deeply associated with the history of this country. After the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan attacked informal Columbus Day celebrations for the same reason: Italians were seen as the “wrong kind” of immigrant community.

By 1869, Italians in South Philadelphia began celebrating Columbus Day with an annual festival hosted by the Societá di Unione e Fratellanza Italiana (United Society of the Brotherhood of Italians), a mutual aid society that had been established two years earlier. The Philadelphia Evening Telegraph reported that the group held a parade that day without incident, but Italians were not so warmly received in other areas of the country. After eleven Italians were lynched in New Orleans in 1891, President Benjamin Harrison sought to ease tensions between the immigrants and the native-born. He declared the first nationwide celebration of Columbus Day the following year, the 400th anniversary of the historic voyage.

The celebration gained prominence in the years following. Here in Philly, a statue of Columbus was commissioned through the donations of local Italian-Americans, displayed at the Centennial Exposition in 1876 and later moved to Marconi Plaza. At the national level, Congress passed a law requesting the President to proclaim the holiday annually, which every president dutifully did until this year. It became a full-fledged federal holiday in 1971 after years of lobbying by Italian-Americans. Not long thereafter, we began to see the backlash against Columbus and those who honor him.

The fusion of themes makes it difficult to understand everyone’s motivations, but it also tells a powerful story. Columbus was once widely praised and centuries later his fellow Italians used his tale to show how they, too, were a part of America’s story. That assertion was rejected by racists and nativists, but ultimately won the day as greater Italian immigration not only gave them and their descendants a greater voice but also made them a constituency with whom politicians wished to curry favor.

In Philadelphia, that was especially true. By the time Columbus Day became a federal holiday, an Italian immigrant, Paul D’Ortona, was President of City Council. The following year, Philadelphia had its first Italian-American mayor, Frank Rizzo. Philadelphia sent an Italian American to Congress in 1980 when Tom Foglietta was elected to represent the 1st district. The message of Columbus Day celebrations — and the larger message of the American melting pot — was borne out. The arguments of nativists were defeated and Italians, at least in Philadelphia, were finally accepted.

This all happened just in time for “being accepted” to become a liability. Columbus, like many of those once deemed heroic, is on trial for his offenses against 21st-century morality. Statues are coming down everywhere in America, some for worse reasons than others. Now, as Christine Flowers notes this week in these pages, the Marconi Plaza statue is under threat. The product of donations from an immigrant community, it is now pilloried as a symbol of oppression. Fifty years ago, Italians in Philadelphia could celebrate the election of one of their own as mayor; today, Mayor Jim Kenney so reviles them that he is willing to violate a court order to keep the Columbus statue shrouded in plywood.

Columbus was once an exemplar used to show that Italians are part of America. Now, the script is flipped, and modern progressives are willing to destroy an Italian-American cultural festival to show off their social justice credentials. Meanwhile, the larger message of immigration, assimilation, and the idea that we are all Americans, is lost. Italian-Americans became fully accepted as part of this nation’s fabric, just as that fabric is being torn into shreds by radicals who can only see America’s flaws.

Philadelphia’s part in that puritanical cleansing is especially disappointing considering how large a role Italians play in the city’s life and history. The way things are going, the federal holiday will soon disappear, but Philadelphians must try to keep the festival alive as it began: in the hearts of the people. The mayor and the elites no longer care about this community, but we can still care for ourselves.