Philadelphia is a city known for being the birthplace of many things.

It is the first planned city in North America. It is home to the first public library, hospital, art museum and mint, among a host of other precedents. Hell, Ben Franklin discovered electricity here.

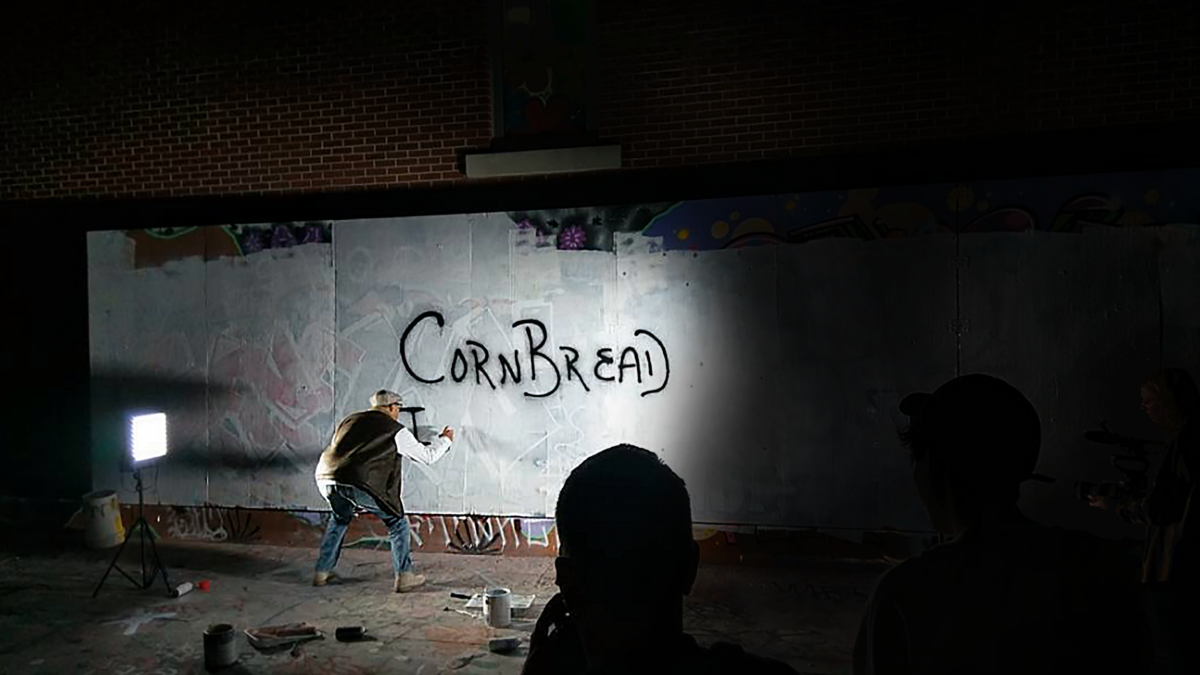

However, there is Philly history that has been made that hasn’t made it into the textbooks. Graffiti has been around since ancient times, but would you believe me if I told you that the origins of hip-hop and street art as we know them today can be traced to Philly? To get that answer, you’d need to talk to none other than Darryl “Cornbread” McCray, the Godfather of Graffiti.

McCray hails from Brewerytown, but he made a name for himself by tagging walls all over the city with his Cornbread moniker in the mid-60s. He earned his name and started his practice while serving time as a youth in a local detention center. Dismayed by the stale, white bread the inmates would be served with their meals, McCray would pester the head cook, Mr. Swanson, for days to prepare some cornbread like his beloved grandmother would make, to no avail.

One day, Mr. Swanson got fed up and got physical. “He damn near lifted me off the floor trying to manhandle me,” remembered McCray. Mr. Swanson then threw McCray out into the chow hall in front of his counselors and peers saying, “Keep this Cornbread out my kitchen!”

From then on, people started teasing McCray by calling him Cornbread, but he thought the name had a ring to it.

“I didn’t mind them calling me Cornbread,” he said. “I went back to my unit and printed Cornbread on the back of my shirt.”

McCray won favor with the gangs in the facility because, inspired by poetry books that his sister would send him and his older brother’s written correspondences with love interests that he would read, he would write love letters for them to send to their girlfriends. After a while, McCray started writing “Cornbread” on the facility walls next to their gang names.

“When I saw their names written on the walls, I would write my name right next to theirs real big,” reflected McCray. “They didn’t never say nothing about it because we were real cool like that.”

Gangs have always used graffiti as a means to establish territories, but McCray simply writing his nickname was something new.

“Gang members wrote on the walls to identify their turf,” said McCray. “I wrote my name on the walls for the sole purpose of establishing a reputation.”

Soon, Cornbread would cover the facility. “I wrote my name all over,” he said. “The bathroom, the chapel, the cafeteria, the gym, the commissary, the administration, the nurse’s station, the gym. I wrote my name everywhere.”

“I knew that if you walked the bus routes, you had a whole bus full of people, and every time it stops, you’ll read my name,” he said. “You couldn’t help but read my name because I was the only one doing it. The whole town belonged to me. I demand your attention. I had to have it. You had no choice but to give me your attention.”

– Graffiti artist Darryl “Cornbread” McCray

This practice would eventually land McCray in the hole after he refused an ultimatum to clean his writing off the walls. The counselors thought he had a mental problem, and he was scheduled to see a psychiatrist. He remembers bucking the session and saying, “You ain’t seen nothing yet. Wait ’til I get outta here. I’m going to set the world on fire!”

He kept true to his word when he got home in 1967. His weapon of choice switched from a magic marker to a can of spray paint. He started when he developed a crush on one of his classmates named Cynthia in the eighth grade at Strawberry Mansion Junior High. He successfully gained her affection by tagging “Cornbread Loves Cynthia” along the route they would take on their walk home.

From there, he would walk the bus routes tagging Cornbread at all the stops.

“I knew that if you walked the bus routes, you had a whole bus full of people, and every time it stops, you’ll read my name,” he said. “You couldn’t help but read my name because I was the only one doing it. The whole town belonged to me. I demand your attention. I had to have it. You had no choice but to give me your attention.” His tag would soon be added to the subway, cabs, freight trains, mail trucks and police vehicles. Everywhere I went, I walked and I wrote. All over the city of Philadelphia,” he said.

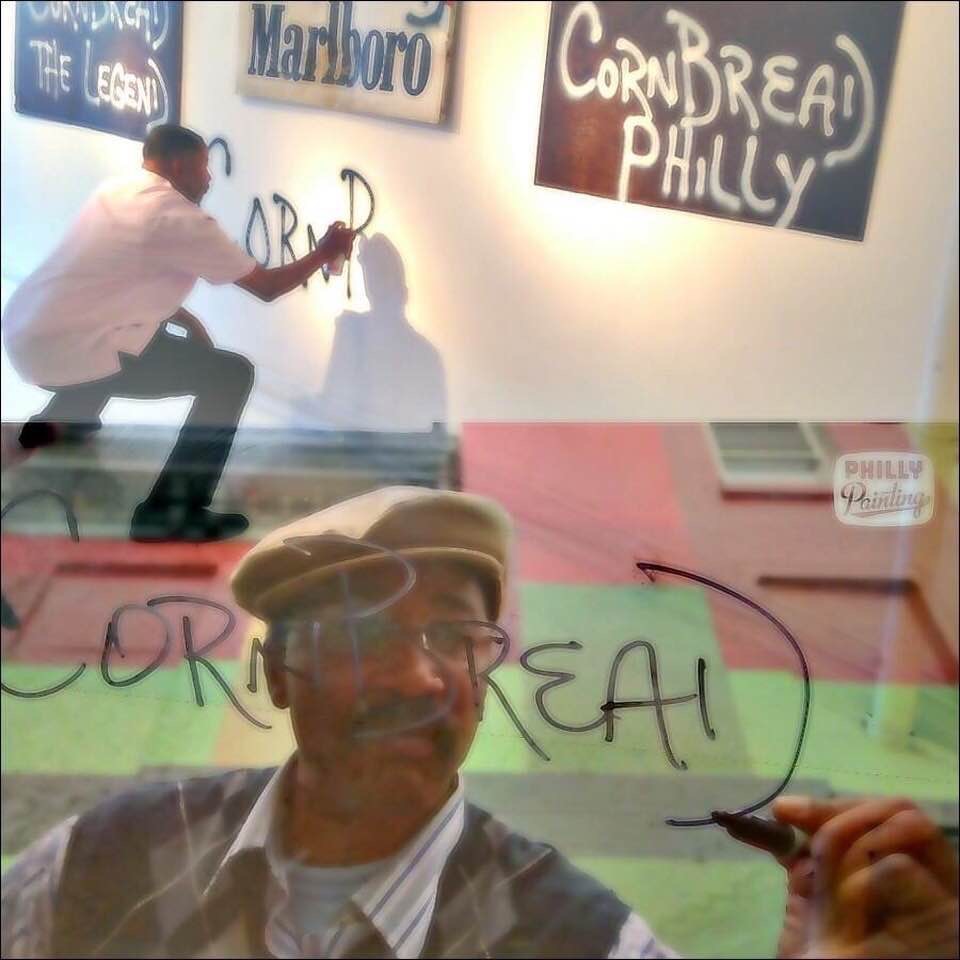

McCray’s antics would soon gain the attention of publications in the city. He would go on to tag the Jackson Five’s airplane, a skyscraper and even a live elephant in the Philadelphia Zoo (decades before Banksy’s elephant). Many names would follow Cornbread on Philly’s walls such as Kool Klepto Kidd, Dr. Cool No. 1, Chewy, Tity, Bobby Cool and Cold Duck (to name a few), but McCray is always touted as the first.

“As far as who started first, I would say Cornbread because he was two years older,” said legendary Philly graffiti artist Cool Earl in the 2010 documentary “Sly Artistic City.”

At the time (the 1960s), there was a movement brewing in the city composed of scores of young, Black teenagers. They organized themselves into groups named after Black Greek fraternities. McCray belonged to Delta Phi Soul for example. These groups were for kids who didn’t want to be in gangs. In addition to graffiti writing, the groups would compete with each other to see who could be best dressed and who had the dopest dance moves before breakdancing was fashionable. They would also spit rhymes to each other without beats before rapping became popular.

“It was something like 150,000 strong teenagers all over the city. North, South, West, Germantown, Mt. Airy. The whole city was a movement,” he said. “It was a totally different mindset, a totally different way of life and we held true to that.” He added, “That was the first wave of the hip-hop revolution.”

How that revolution spread to New York City has never really been explained. It would make sense that New Yorkers got wind of this new phenomenon at an annual convention in Atlantic City called Omega By The Sea where the Philly youths would pile into hotel rooms and do their thing before the casinos were built. Nevertheless, NYC, with its glitz and glam, became known as the birthplace of hip-hop culture after DJ Kool Herc’s groundbreaking turntablism in the Bronx and icon Fab Five Freddy combined the elements of graffiti, DJing, rapping and breakdancing in the late 1970s.

“When that movement migrated, it migrated to New York, and the Bronx put a title on it. They didn’t invent nothing, because when we were doing our thing, in New York, it was [the heroin epidemic like in] ‘American Gangster,’” he said. “The foundation was already established.”

“As people start to build collections of graffiti and street art, I find them coming to us and saying, ‘How can I have this collection and not have something by Cornbread?’”

– Sara McCorriston, co-founder and curator of Paradigm Gallery & Studio

New York graffiti artists took graffiti and expanded on it, adding street numbers, stylized lettering and eventually imagery (though McCray is credited with adding the crown to his tag first), which was gradually accepted into galleries and collections. McCray’s influence can be seen in the burgeoning street art scene with artists like the late Jean Michel-Basquiat and Keith Haring, as well as newer stars like Banksy and Shepard Fairey. Though McCray’s work was word-based and theirs are more image-based, the tenets of street art (the secrecy, illegality, ephemerality, precision, shock value, etc.) are rooted in Cornbread being scrawled on walls in Philadelphia so many years ago.

McCray has been getting to his piece of the street art pie by selling his work in the form of canvases, signs, street maps, T-shirts and more tattooed with his name and slogans. As time has progressed and more information has become available, McCray’s name has started to ring across the globe. He is currently represented by Paradigm Gallery & Studio in Queen’s Village, where his tagged signs are selling.

“There’s a worldwide demand for his artwork. He has this international following knowing who he is,” said Paradigm co-founder and curator Sara McCorriston (who is also working to tell the story of Isaiah Zagar whose “uncommissioned” mosaic street art also appeared in Philadelphia in the 1960s). “As people start to build collections of graffiti and street art, I find them coming to us and saying, ‘How can I have this collection and not have something by Cornbread?’”

Locally, McCray’s legacy can be seen on the thousands of murals sprawling across the city by the illustrious Mural Arts Program, an extension of Mayor Wilson Goode’s Anti-Graffiti Network. McCray has worked with both organizations (as well as the Graffiti Alternatives Program previously), which were started to clean up the city dubbed “The Graffiti Capital Of The World” by The New York Times in 1971 and transform the young vandals’ talents into marketable skills.

“The city of Philadelphia was so messed up, it looked like another world,” McCray said of the time when the graffiti got out of control. “When I started writing on walls, it didn’t look like that. Something needed to be done. We had to clean our house. This is where we live.”

All-in-all, McCray’s wall writing served as a means for voiceless, Black kids in the ghetto to be heard. Though deemed destructive, his application of aerosol paint to brick walls made him somebody in a world that didn’t want to know he existed. Every graffiti writer who followed wanted the same thing: to be realized. McCray’s experience pioneering and the Philly scene from his time is surely worthy of the silver screen.

“At the end of the day, I’d like to be recognized fully for the culture that I gave birth to,” he said. “There was no hip-hop artist before me. There was no graffiti artist before me. All roads lead back to me.”

Darryl “Cornbread” McCray can be followed on Instagram at @cornbreadthelegend. To purchase his art email [email protected] or visit Paradigm Gallery & Studio.