A hut, a bird blind and three benches — well-crafted and distinctive — were built in the Pennypack Environmental Center last year. Titled Embodying Thoreau, it’s part of the Fairmount Park Art Association’s New Land Marks program, which joins artists with communities to create new public artworks. The response of visitors encountering these pieces will vary, but they will offer a slightly new and different glimpse of the world. This, of course, is the purpose of art. And the purpose of public art is to make this opportunity available to every one of us, for free, as we go about our daily activities.

Embodying Thoreau is merely one recent addition to the vast array of public art that makes Philadelphia the nation’s leader. Yet we Philadelphians are largely oblivious to treasures that lie right under our noses, traveling abroad to admire someone else’s art and culture in the belief that we have nothing like it at home. On a recent visit to Paris, I found myself in awe of the city’s art and architecture, but I was also impressed by two other things: the knowledge and pride typical Parisians have for their city’s assets and the number of books, maps and guides that ensure these assets are recognized and respected.

Believing that some remedial education about Philadelphia’s public-art collection will promote justifiable civic pride and, more importantly, give us joy from what we already have, consider this: Philadelphia has more public art than any other American city, the result of almost two centuries of notable civic leadership by individuals, organizations and agencies who have given Philadelphia a long list of “firsts.”

Philadelphia artists and architects have graced the city with sculpture and ornament second to none. City Hall and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts are well-known examples in a tradition extending back to the early 19th century and works such as William Rush’s allegories of the Schuylkill River installed for beautification and public enjoyment at the Water Works.

The tradition continued with the 1872 establishment of the Fairmount Park Art Association, a private organization and the nation’s first dedicated to integrating public art and urban planning. It is best known for its art along the Schuylkill River drives.

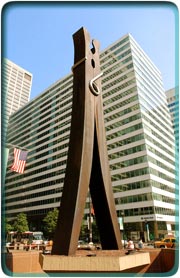

The city’s Redevelopment Authority (RDA) has generated around 450 works, including Oldenburg’s Clothespin, through its “percent for art” program which requires private developers working with the RDA to give something back to the citizens in the form of public art. This groundbreaking 1959 program to make Philadelphia “beautiful as well as livable” was the first of its kind. It has been copied all over the country.

The Philadelphia Office of Arts and Culture, sadly a victim of the city’s recent budget cuts, had its own percent-for-art program. Though less active than the RDA’s, after which it was modeled, the program was nearly as old.

The Department of Recreation’s Mural Arts Program started in 1984 as an outgrowth of the anti-graffiti network. Having created more than 2,300 murals — giving Philly more murals than any other city and making it a national model — MAP offers tours of works that beautify neighborhoods and help build community.

And finally, we have benefited from an abundance of private institutions — universities, hospitals and businesses — whose sense of civic leadership and pride led them to place private art, such as the Wanamakers’ Eagle and the Curtis Building’s Dream Garden, in public places for the enjoyment of us all.

How much does Philadelphia’s public art matter? Imagine City Hall without Billy Penn, JFK Plaza without Love, the Parkway without Swann Fountain and Rittenhouse Square without its Goat.

If we are to be good stewards who continue this legacy, we need to protect what we’ve received and augment it with our own distinct contributions. Both activities depend on public awareness, appreciation and pride. Had we more of each of these characteristics, I imagine Philadelphia could have collectively found a way to keep the Calder Eagle, which, for the short time it sat in the Museum of Art courtyard, majestically demonstrated the power of the perfect piece of public art perfectly sited.

Despite this missed opportunity, we have many riches to celebrate, but user-friendly information is scarce. While a citywide locator map would be great, two Web sites can get you started: the Fairmount Park Art Association (www.fpaa.org) and the Mural Arts Program (www.muralarts.org) both have pictures, directions and background information for many of their pieces.

Take a look. You might still want to visit Paris, but it won’t be because you think there’s nothing worthwhile here at home.

Joanne Aitken is an architect and member of Philadelphia’s Design Advocacy Group.