On March 29, 1988, an album that propelled two kids from West Philadelphia into the stratosphere of international fame was released on Jive Records: DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince’s He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper. Their debut LP, 1987’s Rock the House, included the mild hit single, “Girls Ain’t Nothing But Trouble,” but it was the duo’s sophomore effort, which eventually sold enough to be certified triple platinum, that ranks among the most successful hip-hop records ever—and certainly the most successful out of Philadelphia.

He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper made Jeffrey Townes and Will Smith household names throughout their beloved hometown, while subsequently putting Philly on the map and the global stage in ways that still resonate a quarter-century later. Townes remains one of the most respected spinmasters in the world, and Smith has become one of the highest grossing actors in Hollywood and part owner of the 76ers.

But DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince were absolute underdogs at the time. They were making rap music, but didn’t sound like anyone else, didn’t look like anyone else and almost didn’t fit in—except that they did. Why? Because they were “regular kids from the neighborhood” that hip-hop could relate to. What set them apart was that they were making music that was slightly ahead of the curve.

Back then, a lot of good music was coming out of Philadelphia, but New York City had hip-hop on lock. In fact, to the rest of the country, hip-hop coming out of anywhere from Boston to Philadelphia was known as “New York rap.” But what Philadelphia did have was DJs. Everyone knew that DJing here was pure art. Sure, it’s an art form anywhere it’s done well, but in Philly, DJing was taken to the next level. Hip-hop DJs were known for cutting and scratching the records, which means moving the vinyl LPs back and forth on the turntable to create a completely different sound. (If you needed that explanation, you should probably learn more about the history of hip-hop.) But instead of just creating sounds to complement the actual recording, Philly DJs would make entirely new beats using the scratching sound. Instead of their hands, they would cut with their elbows, their chin or even a sneaker—anything to put on a good show. Performances often would consist of an emcee not rapping, but just touting what his DJ was about to do next.

DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince didn’t follow the New York model for rap groups: an emcee backed by a DJ who kind of just stood around and placed records on and off the turntables. Those two showcased the DJ in a way that no one else was doing. They stood out partly because they had a creative stage show, but mostly because they put DJ Jazzy Jeff front and center, making his scratching and cutting the most anticipated part of their act. And no one did it as skillfully.

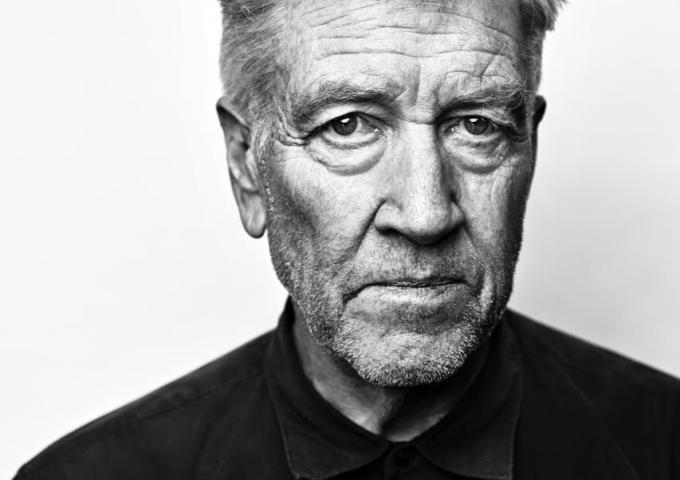

Jeff still travels all over the world DJing shows and parties, forever representing Philly via his ever-present Phillies cap. But before his most recent sojourn, he shared a few memories with PW about the time he and Smith spent hotel-bound in England recording He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper and the exciting period before—and during—its release in 1988, recalling their Grammy Awards boycott and everything from those initial “for-the-suburbs” criticisms to the night he got caught with his pants down.

When it was time to do the second album, [our record label] Jive was like, “Listen, we want you guys to go to London. We have some people; we have studios over there. We just think you should go.” And we were like, “Wow!”

So, I packed up my drum machines and all the rest of that stuff and got ready to go. It was crazy because I actually got into a car accident with Lady B, the radio personality, and shattered my kneecap about a month before we were supposed to go. I had a cast from my hip to my ankle, going to London to do this album.

The first night we get there, we find out that a really big Def Jam tour was over there, with Public Enemy and a bunch of other artists. Of course, we had done shows with these guys, so we decided we were gonna just show up. So, we go to the club, and everybody in line is like, “Oh shit! That’s Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince!” We walk up, and the guy at the door says, “We don’t allow cripples in here.” We try to explain to him who I am, but he wouldn’t let us in. He didn’t believe us. We all ended up leaving, and I ended up jumping in the cab with a broken leg and going back to the hotel.

I had all my equipment set up in the hotel room, and I would make beats there. Will would write, and we would take it to the studio that night. We worked pretty much from about 4 in the afternoon to about 5 in the morning. We were there for a month, and I saw daylight maybe about four or five days. We would go to the studio and work, and by the time we came out, we would get back to the hotel just in time to go to breakfast, then to the room to go to sleep. Then we’d wake up and go back to the studio.

That schedule worked for us. I made “Brand New Funk” one morning going to bed. They had guys over there that would help us; I would make stuff and a guy would end up playing bass lines and stuff over it.

Before we started on that album, we were in the process of doing a DJ album, and we already had those songs done, so when we started recording songs for He’s the DJ, I’m the Rapper, I was like, “Yo, why don’t we put both of these albums together and just do a double album?” It was kinda funny because no one had ever thought to do that. We just made the suggestion, and Jive was like, “Yo, that might be great. It would be the first rap double album.”

So, we already had half of that done, and we just started piecing together the songs and figuring out which ones we were gonna have on the record. One of the shows that we did was at Union Square in New York, and it just so happens that [New York radio DJ] Mr. Magic taped it. I just did a DJ routine and didn’t even think anyone was taping it. We did that at every show. He started playing the show on the radio, and people were calling in and requesting that part. It got so big that it really helped me as a DJ, especially in New York. So, we called Mr. Magic and asked if we could have a copy of the tape because I had suggested we put that on the album, too. So “Live at Union Square” was actually a cassette recording of us performing at Union Square.

We sat in the studio and compiled all of the records and started mixing it and tried to figure out what we wanted to put out first. We were trying to do something that was a little bit harder, with some scratches in it, maybe some human beatbox stuff, and I remember one of the producers who was working with us saying, “‘Parents Just Don’t Understand’ should be the first single.”

Me and Will were like, “No, no, no, no, no.” And he was just like, “I’m telling you, ‘Parents Just Don’t Understand’ is a smash hit.”

It was really, really interesting how that was not our favorite record at all, but he had been around a little bit, and we were smart enough to know that even though we may not agree, he may know what he was talking about. It wasn’t like we did any records on the album that we hated; there were just records we liked more.

We had been in London for a month, and I had exceeded the time my cast was supposed to be on, and it started irritating my leg. One night, Will was like, “Listen, man. I can get your cast off.” So, he called downstairs and ordered about 25 butter knives. I pulled my pants down and was in my underwear, and he proceeded to try to saw my cast off. He got it halfway, and then he ripped it. He couldn’t get it completely off, so the cast was looking like a budding flower, and I couldn’t get my pants on or nothing. He was laughing because he didn’t know what to do. I couldn’t leave the hotel like that to go to the hospital to have them cut it off, so we ended up having to track [then-acting manager and their friend from Philly] James Lassiter down. JL ended up coming in and taking a steak knife and sawing it off. JL tells that story to this day.

Finally, it was time to go home.

Back in the U.S., right before the album came out, we did a show in Columbus, Ohio. It was with Whodini and somebody else, and Russell Simmons was there. We approached Russell right there and told him that we were really big fans, and we needed a good manager—somebody that’s gonna do something. We told him that we would appreciate it if he would just watch the show, and we could talk to him after.